There are all kinds of technology that appear through the ages that find immediate success, promise to revolutionize the world, but fade to obscurity almost as quickly. Things like the ZIP disk, RDRAM, the digital compact cassette, or even Nintendo’s VirtualBoy. Going even further back in time [smbaker] is taking a look a bubble memory, a technology that was so fast and cost-effective for its time that it could have been used as “universal” memory, combining storage and random-access memory into a single unit, but eventually other technological developments overshadowed its quirks.

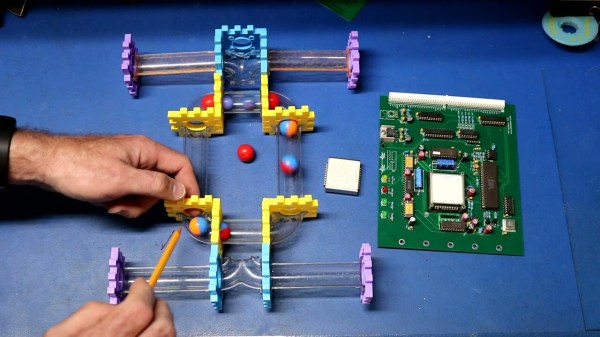

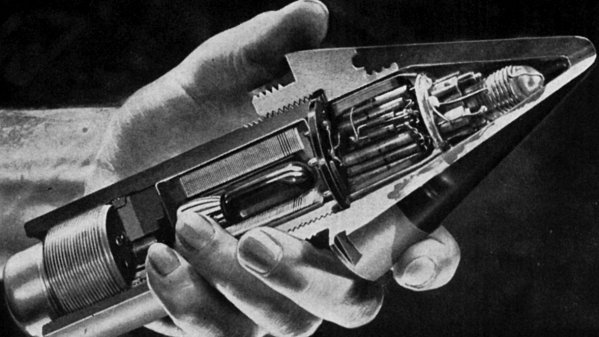

[smbaker] is placing his magnetic bubble memory module to work in a Heathkit H8, an Intel 8080-based microcomputer from the the late 70s. The video goes into great detail on the theory of how these devices used moving “bubbles” of magnetism to store information and how these specific devices work before demonstrating the design and construction of a dedicated support card which hosts the module itself along with all of the necessary circuitry to allow it to communicate with the computer. From there he demonstrates booting the device using the bubble memory and performs several write and read actions using the module as a demonstration.

Eventually other technologies such as solid-state RAM and various hard disk drives caused the obsolescence of this technology, but it did hang on for a bit longer in industrial settings due to its ability to handle high vibrations and mechanical shocks, mostly thanks to the fact that they had no moving parts. Eventually things like Flash memory came around to put the final nail in the coffin for these types of memory modules, though. The Heathkit H8 is still a popular computer for retrocomputing enthusiasts nonetheless, and we’ve seen all kinds of different memory modules put to work in computers like these.

Continue reading “Magnetic Bubble Memory Brought To Life On Heathkit”