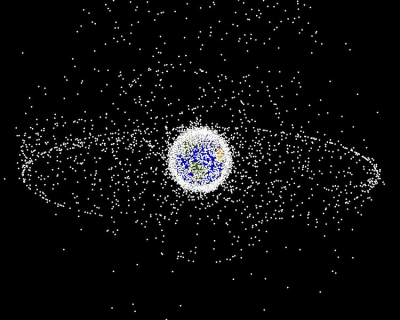

With the notable exception of the Space Shuttle, rockets and spacecraft have always been considered disposable. It’s a slow and expensive way to travel, akin to building a new airliner for every flight, but it was the easiest option. These vehicles have always represented the pinnacle of engineering and material science of their time, and just surviving the trip to space once was an incredible accomplishment. To have another go around would have been asking too much of the technology. Even looking back on the Space Shuttle program, there’s plenty of debate about whether or not the reusable design really paid off in the end.

So SpaceX’s ability to land, refurbish, and refly the first stage of their Falcon 9 booster is no small accomplishment. After demonstrating the idea was possible in 2017, the company made numerous changes to the latest iteration of the rocket with reusability in mind. Known as Block 5, this version of the Falcon 9 is designed to be more survivable and require minimal servicing between flights. The company says its cheaper and faster to reuse the Block 5 than it would be to build a new one for each flight, allowing the company to approach spaceflight more like commercial aviation.

With a fleet of Block 5 boosters now in rotation, SpaceX has given them serial numbers not unlike an airplane’s tail number. It might not be the kind of thing the general public would normally be aware of, but these serial numbers have allowed a dedicated community of space aficionados to keep track of the missions each booster has flown.

Unfortunately the story of one of these rockets, officially referred to as “Cores” in SpaceX parlance, was recently cut short. Core B1056, returning from the Starlink 4 mission on February 17th, failed to land on the autonomous spaceport drone ship (ASDS) Of Course I Still Love You and splashed down in the ocean. It’s still unclear what condition the booster was in after its soft landing in the water, but when the recovery ships returned to port empty handed, there was no question as to the fate of B1056.

From a purely business standpoint, the failure of any of SpaceX’s boosters means lost time and revenue. But in some ways B1056 had established itself as the vanguard of the fleet, managing to either set or break a number of records in its relatively short life. The destruction of the most thoroughly flight proven Block 5 booster is a stark reminder that there’s very little about spaceflight that could be called routine.

Continue reading “A Farewell To Hackaday’s Favorite Falcon 9 Booster”