Here at Hackaday, we love projects that result in useful lab equipment for a fraction of the cost of professional gear. [Lorenz], over at Advanced Tinkering, built his own instrument for Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy, or LIBS, and it’s quite an impressive device. LIBS is a technique for analyzing substances to find their chemical composition. Basically, the idea is to zap a sample with a powerful laser, then look at the little cloud of plasma that results and measure the wavelengths emitted by it.

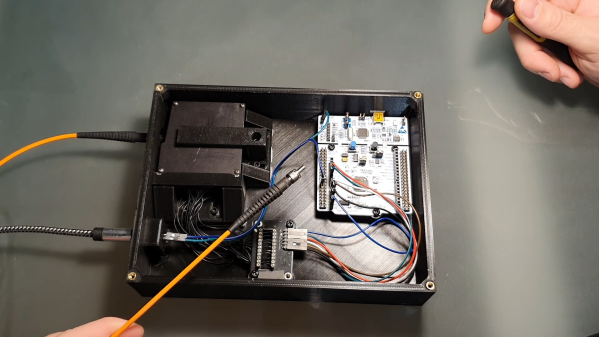

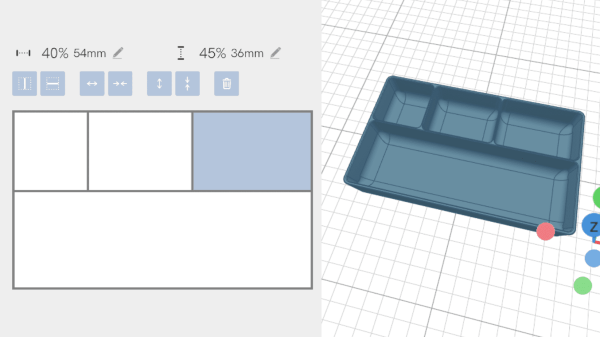

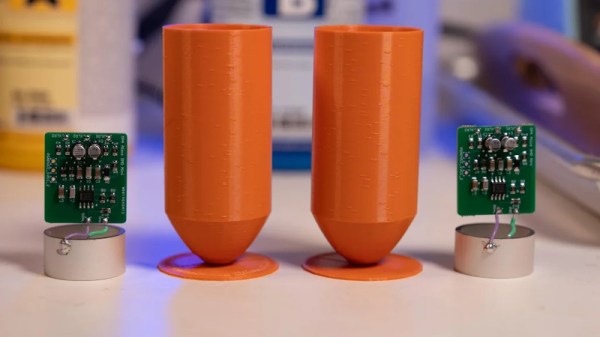

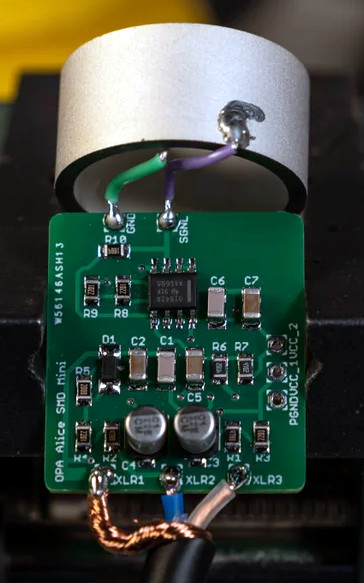

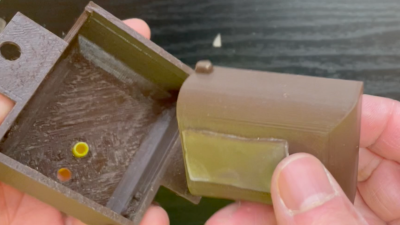

The laser [Lorenz] used is a Nd:YAG unit salvaged from a tattoo removal machine. After it fires a pulse, a photodiode detects the light and triggers a spectrometer, which consists of a diffraction grating, a few lenses and mirrors, and a linear CCD sensor. The grating splits the incoming lights into its constituent components, which fall onto the CCD and trigger its pixels. An STM32 Nucleo board reads out the results and sends them to a PC for further processing.

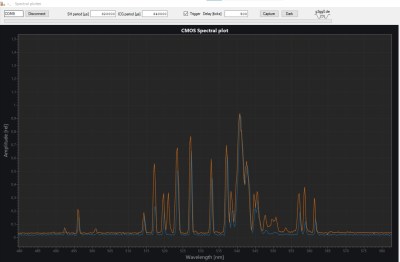

That processing bit turned out to be a full project on its own. [Lorenz] called upon [g3gg0], who software that simplifies the operation of the spectrometer. First, it helps with the instrument’s calibration. Point the detector at a well-known light source like a laser or a fluorescent lamp, then select the expected wavelengths on the resulting spectral plot. The software then automatically calculates the correct coefficients to map each pixel to a specific wavelength.

The software also contains a database of spectra corresponding to chemical elements: once you’ve taken a spectrum of an unknown sample, you can overlay these onto the resulting plot and try to find a match. The resulting system seems to work quite well. Samples of iron oxide and silver oxide gave a reasonable match to their constituent components.

We’ve seen other types of spectrometers before: if you simply want to characterize a light source, check out this Raspberry Pi-based model. If you’re interested in chemical analysis you might also want to look at this open-source Raman spectrometer.

Continue reading “Spectrometer Detects Chemicals By Zapping Samples With A Laser Beam”