If you want to measure radioactivity, nothing really beats a Geiger counter: compact, rugged, and reasonably easy to use, they’re by far the most commonly used tool to detect ionizing radiation. However, several other methods have been used in the past, and while they may not be very practical today, recreating them can make for an interesting experiment.

[Mirko Pavleski] used easily obtainable components to build one such device known as an alpha radiation spark detector. Invented in 1945, a spark detector contains a strong electric field into which discharges are triggered by ionizing radiation. Unlike a Geiger-Müller tube, it uses regular air, which makes it sensitive only to alpha radiation; beta and gamma rays don’t cause enough ionization at ambient pressure. Fortunately, alpha radiation is the main type emitted by the americium tablets found in old smoke detectors, so a usable source shouldn’t be too hard to find.

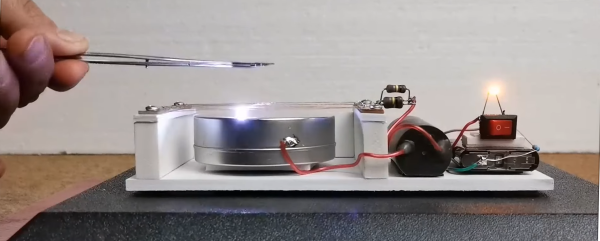

The construction of this device is very simple: a few thin copper wires are suspended above a round metal can, while a cheap high-voltage source provides a strong electric field between them. Sparks fly from the wires to the can when an alpha source is brought nearby; a series resistor limits the current to ensure the wires don’t overheat and melt.

Although not really practical as a measurement device, the spark detector can nevertheless be used to perform simple experiments with radioactivity. As an example, [Mirko] demonstrates in the video embedded below that alpha particles are stopped by a piece of paper and therefore present no immediate danger to humans. The high voltage present in the device does however, so care must be taken with the detector more than with the radiation source.

We’ve seen several homebrew Geiger counters, some built with plenty of duct tape or with the good old 555 timer. But you can also use photodiodes or even certain types of plastic to visualize ionizing radiation.

Continue reading “Detecting Alpha Particles Using Copper Wire And High Voltage”