Historically gaming consoles are sold at little-to-no profit in order to entice customers with a low up-front price. The real profits roll in afterwards from sales of games and accessories. Seeking a slice of the latter, aftermarket accessory makers jump in with reverse-engineered compatible products at varying levels of “compatible”.

When the Nintendo Switch was released with a standard USB-C port for accessories, we had hoped those days of hit-or-miss reverse engineering were over, but reality fell short. Redditor [VECTORDRIVER] summarized a few parts of this story where Nintendo deviated from spec, and accessory makers still got things wrong.

Officially, Nintendo declared the Switch USB-C compliant. But as we’ve recently covered, USB-C is a big and complicated beast. Determined to find the root of their issues, confused consumers banded together on the internet to gather anecdotal evidence and speculate. One theory is that Nintendo’s official dock deviated from official USB-C dimensions in pursuit of a specific tactile feel; namely reducing tolerance on proper USB-C pin alignment and compensating with an internal mechanism. With Nintendo playing fast and loose with the specs, it makes developing properly functioning aftermarket accessories all the more difficult.

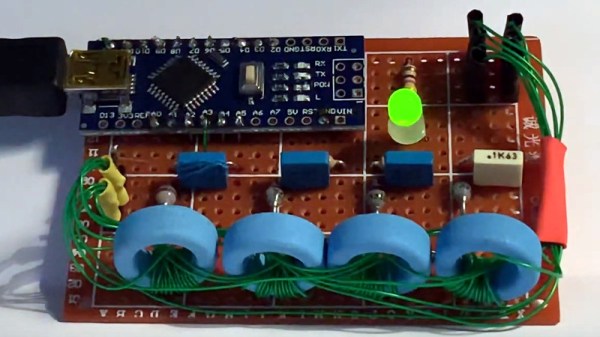

But that’s not the only way a company can slip up with their aftermarket dock. A teardown revealed Nyko didn’t use a dedicated chip to manage USB power delivery, choosing instead to implement it in software running on ATmega8. We can speculate on why (parts cost? time to market?) but more importantly we can read the actual voltage on its output pins which are too high. Every use becomes a risky game of “will this Switch tolerate above-spec voltage today?” We expect that as USB-C becomes more common, it would soon be cheapest and easiest to use a dedicated chip, eliminating the work of an independent implementation and risk of doing it wrong.

These are fairly typical early teething problems for a new complex technology on their road to ubiquity. Early USB keyboard and mice didn’t always work, and certain combination of early PCI-Express cards and motherboards caused damage. Hopefully USB-C problems — and memories of them — will fade in time as well.

[via Ars Technica]

[Main image source: iFixit Nintendo Switch Teardown]