3D printers are an excellent tool to have on hand, largely because they can print other tools and parts rapidly without needing to have them machined or custom-ordered. 3D printers have dropped in price as well, so it’s possible to have a fairly capable machine in your own home for only a few hundred dollars. With that being said, there are some limitations to their function but some of them can be mitigated by placing the printer head on a robot arm rather than on a traditional fixed frame.

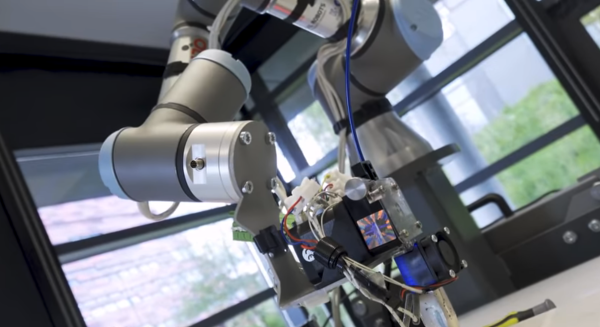

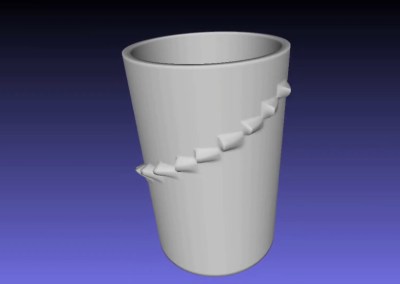

The experimental 3D printer at the University of Nottingham adds a six-axis robotic arm to their printer head, which allows for a few interesting enhancements. Since the printer head can print in any direction, it allows material to be laid down in ways which enhance the strength of the material by ensuring the printed surface is always correctly positioned with respect to new material from the printer head. Compared to traditional 3D printers which can only print on a single plane, this method also allows for carbon fiber-reinforced prints since the printer head can follow non-planar paths.

Of course, the control of this printer is much more complicated than a traditional three-axis printer, but it is still within the realm of possibility with readily-available robotics and microcontrollers. And this is a hot topic right now: we’ve seen five-axis 3D printers, four-axis 3D printers, and even some clever slicer hacks that do much the same thing. Things are finally heating up in non-planar 3D printing!

Thanks to [Feinfinger] for the tip!