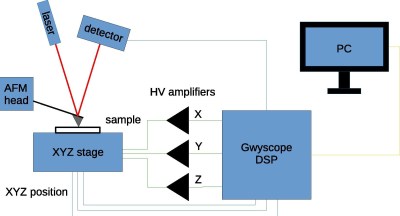

A scanning probe microscope comes in a wide variety of flavors, they all produce a set of data points containing the measurements at each location. Usually these data points form a regular 2D grid, but it can be more beneficial to change the density of measurements at certain locations, or even the height, which creates a much more complex probing path and subsequent (XYZ) data set.

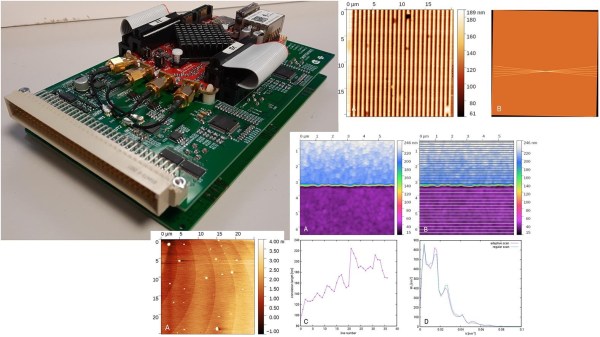

Yet this should not deter anyone, as [Miroslav Valtr] and colleagues demonstrate in a July 2023 article in Hardware X where they use a Red Pitaya SBC along with custom Eurocard-format PCBs to create a low-cost-ish (<1,500 USD) open hardware Digital Signal Processor (DSP) they call Gwyscope.

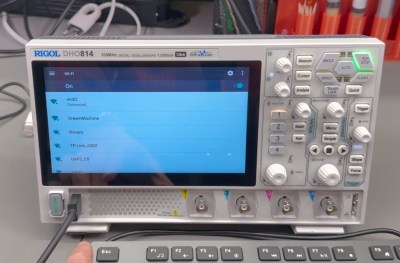

The Red Pitaya itself is used as a convenient hybrid FPGA-based module with on-board signal processing hardware, with its Xilinx Zynq ARM-FPGA chip providing both an FPGA section to implement the feedback loop module in Verilog, as well as the means to run a Linux instance with the C-based software that connects via Ethernet to a remote workstation. This communication is based around the GwyFile library, which is part of the Gwyddion project. The scanning paths are generated using libgwyscan (see this presentation for an introduction).

The resulting scan data is saved as an XYZ data file, which can be read with the Gwyddion visualization and analysis program. Although far from a quick & easy afternoon project for the casual hobbyist, it could be a boon for universities and laboratories.

Thanks to [Nicolae Irimia] for the tip.