Earlier this month a single person pleaded guilty to taking down some computer labs at a college in New York. This was not done by hacking into them remotely, but by plugging a USB Killer in one machine at a time. This malicious act caused around $58,000 in damage to 66 machines, using a device designed to overload the data pins on the USB ports with high-voltage. Similar damage could have been done with a ball-peen hammer (albeit much less discreetly), and we’re not here to debate the merits of the USB Killer devices. If you destroy property you don’t own you should be held accountable.

But the event did bring an interesting question to mind. How robust are USB ports? The USB Killer — which we’ve covered off and on through the years — is billed as a “surge testing” device and operates by injecting -200 volts DC on the data lines of the USB connection. Many USB ports are not protected against this and the result is permanent damage to the computer hardware. Is protection for these levels of abuse necessary or would it needlessly add cost to our machines?

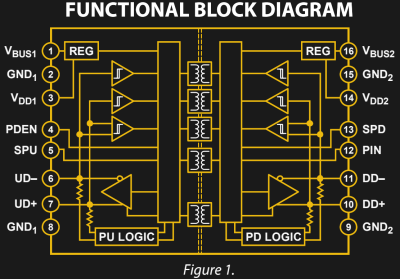

A chip like the TPD4S014 has ESD protection on the data lines that is rated up to +/- 1500 volts, clamping to ground to dissipate the energy. It’s a solution that should protect against repeated spikes on the data lines, as well as short circuits on the power lines and over/undervoltage situations.

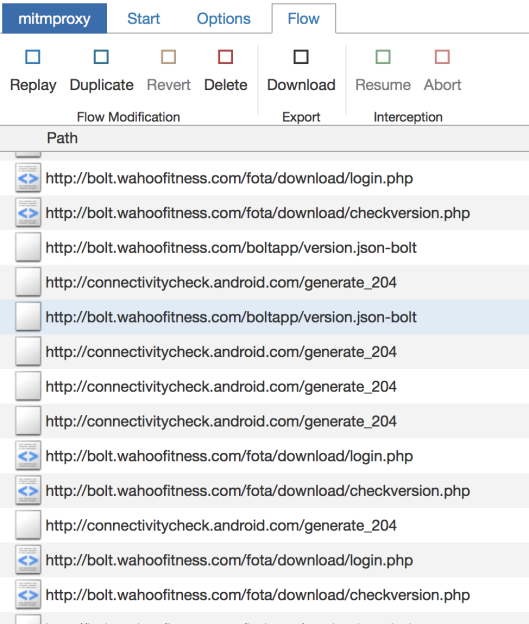

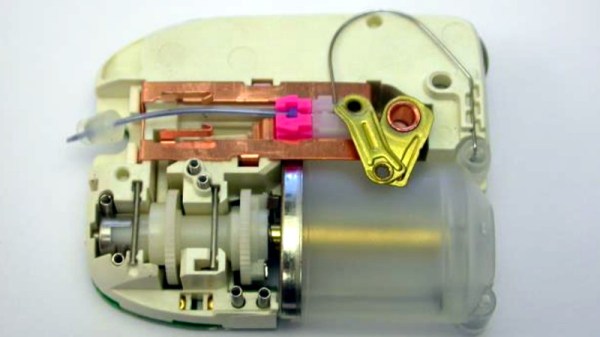

The ADuM4160 is an interesting step up from this. It’s designed to provide isolation between a USB host and the device connected to it. Rather than relying on clamping, this chip implements isolation through air core transformers. Certainly this would be overkill to install in every product, but for those of use building and testing USB devices this would save you from “Oops, wrong USB cable” moments at the work bench.

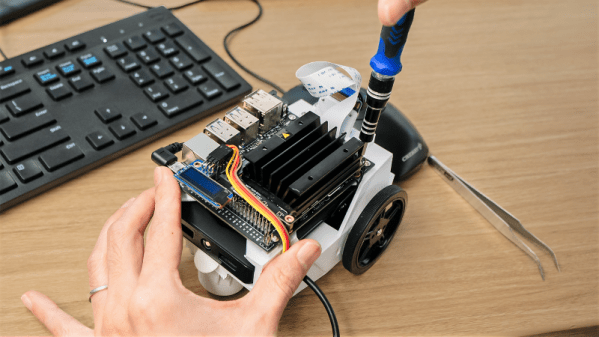

Speaking of accidents at the bench, there is certainly a demand for USB isolation outside of what’s built into our computers. Earlier this year we saw a fantastic take on a properly-designed USB power strip. Among the goals were current limiting, undervoltage protection, and a proper power disconnect switch for each port. The very need to design your own reminds us that consumer manufacturers are often lazy in their USB design. “Use a USB hub” is bad advice for protection at the workbench since quality of design varies so wildly.

We would be interested in hearing from anyone who has insight on standards applying to equipment continuing to survive over current or over voltage events and remain functional. There are standards like UL-60950 that should apply to USB. But that standard includes language about failing safe for the operator, not necessarily remaining functional:

After abnormal operation or a single fault (see 1.4.14), the equipment shall remain safe for an OPERATOR in the meaning of this standard, but it is not required that the equipment should still be in full working order. It is permitted to use fusible links, THERMAL CUT-OUTS, overcurrent protection devices and the like to provide adequate protection.

So, we’re here to ask you, the readers of Hackaday. Are our USB devices robust enough? Do you have a go-to USB protection chip, part, or other circuit you like to use? Have you ever accidentally killed a USB host device (if so, how)? Do you have special equipment that you depend on when developing projects involving USB? Let us know what you think in the comments below.