After a seemingly endless stream of projects that see the ESP8266 open doors or report the current temperature, it can be easy to forget just how powerful the little WiFi-enabled microcontroller really is. In fact, you could argue that most hackers aren’t even scratching the surface of what the hardware is actually capable of. But that’s not the case for [Brian Wagner] and his students from the Kentucky Country Day School.

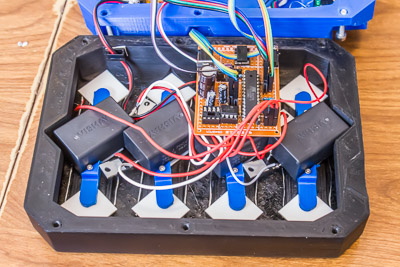

Their project, the GamerGorl, is a completely custom handheld game system running on a Wemos D1 Mini development board. The team’s PCB, which was developed over several iterations, is essentially a breakout board which allows them to easily connect up peripheral devices. Given the low total component cost of the GamerGorl and relative simplicity of its construction, it looks like a phenomenal project for older STEM students.

Their project, the GamerGorl, is a completely custom handheld game system running on a Wemos D1 Mini development board. The team’s PCB, which was developed over several iterations, is essentially a breakout board which allows them to easily connect up peripheral devices. Given the low total component cost of the GamerGorl and relative simplicity of its construction, it looks like a phenomenal project for older STEM students.

Beyond the ESP8266 board, the GamerGorl features a SSD1106 1.3″ OLED display, a buzzer for sound effects, two tactile buttons, and an analog joystick originally intended for an Xbox controller. Around the backside there’s a WS2812B RGB LED strip that’s at least partially for decoration, but it’s also actively used in some of the games such as the team’s take on Simon.

Even if you aren’t in the market for a portable game system, the GameGorl does provide an interesting case study for MicoPython applications on the Wemos D1 Mini. Browsing through the team’s source code as well as the helpful hints that [Brian] gives about getting the software environment up and running could be useful if you’re looking to expand your ESP8266 programming repertoire. We’d also love to see this device running the “ESP Little Game Engine” we covered recently.

Continue reading “Building An ESP8266 Game System With MicroPython”