We are very familiar with retrocomputers, and if you want you too can build a computer that could have been made in the late ’70s on a breadboard. Just grab your CPU of choice, add some RAM, some ROM, a ton of jumper wires, and give it some way to talk to the outside world. The problem with the computers inspired by yesteryear is that they all, inexplicably, use through-hole parts. If only someone used the small QFP parts instead of the big chonkin’ PDIPs, we could have really small retrocomputers. That’s exactly what [NotArtyom] did, and he managed to come up with a wearable 6502 watch.

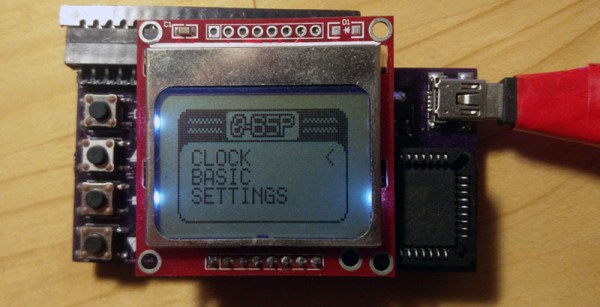

The system design for this 6502-based watch is fairly standard for what you would find in any other retrocomputer. There’s a PLCC 6502, 32k of SRAM, 16k of ROM, and a PLLC’d 6522 for a bit of IO. There are a few peripherals hanging off the 6522, and since this thing is a watch the most important is a real time clock. There’s also a Nokia LCD and a 20-pin Commodore keyboard connector.

Software-wise, most of the ROM is dedicated to G’Mon, a generic monitor that can view and modify memory. There’s also EhBasic, and a kernel to handle the RTC, keyboard, and display.

Whether or not this is a useful smartwatch isn’t the question; this is one of the first retrocomputer projects we’ve seen that lean into the non-PDIP versions of these classic chips. This is a bit surprising, because you can still buy these parts, PDIP or not, new from the usual vendors. If nothing else, it’s a demonstration of what can be done with modern IC packages.