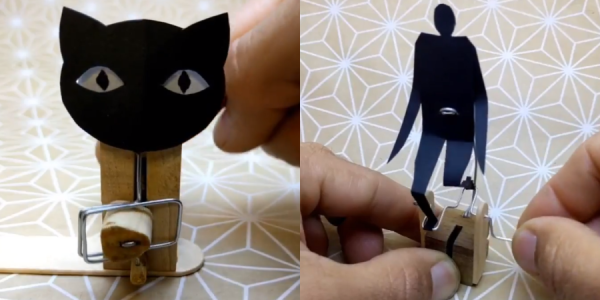

[Federico Tobon] from [Wolfcat Workshop] spent Makevember in 2017 building a series of fascinating automata using the most basic of craft supplies and simple tools in his workshop. Using a combination of rigid materials such as wooden cubes, popsicle sticks, and paper clips and pliable ones like paper and rubber bands, his creations are way more delightful to play with compared to fidget spinners.

There are no assembly guides, instructions or building plans, but for a hacker, one look at these designs ought to be enough to glean how to build one, with some trial and error to get it right. And that is exactly what [Tobon] found to his delight. After sharing animated GIFs of his creations on social media, numerous other hackers built and shared their own versions of his designs as well as building some new ones.

He posts several other useful resources, some of which were the inspiration that got him started making these automata. All of them are pretty interesting, so do take a look at them too. There is a lot that young kids can learn from building these little machines, given some guidance and help from the elders. But the way we see it, it’s likely the old folks will enjoy them more.

The video after the break compiles all of the little machines for six minutes of viewing pleasure.