There’s something compelling about high-altitude ballooning. For not very much money, you can release a helium-filled bag and let it carry a small payload aloft, and with any luck graze the edge of space. But once you retrieve your payload package – if you ever do – and look at the pretty pictures, you’ll probably be looking for the next challenge. In that case, adding a little science with this high-altitude muon detector might be a good mission for your next flight.

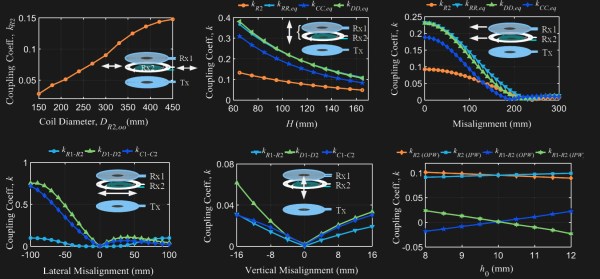

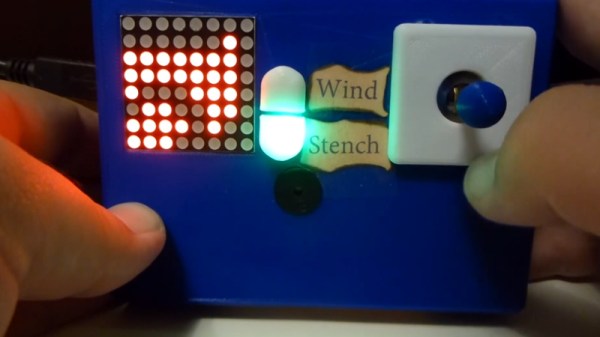

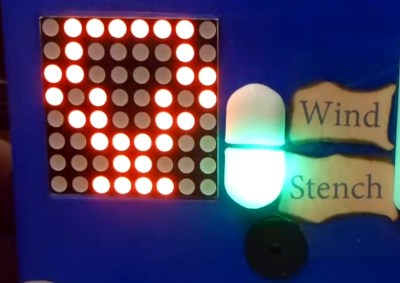

[Jeremy and Jason Cope] took their inspiration for their HAB mission from our coverage of a cheap muon detector intended exactly for this kind of citizen science. Muons constantly rain down upon the Earth from space with the atmosphere absorbing some of them, so the detection rate should increase with altitude. [The Cope brothers] flew two of the detectors, to do coincidence counting to distinguish muons from background radiation, along with the usual suite of gear, like a GPS tracker and their 2016 Hackaday prize entry flight data recorder for HABs.

The payload went upstairs on a leaky balloon starting from upstate New York and covered 364 miles (586 km) while managing to get to 62,000 feet (19,000 meters) over a five-hour trip. The [Copes] recovered their package in Maine with the help of a professional tree-climber, and their data showed the expected increase in muon flux with altitude. The GoPro died early in the flight, but the surviving footage makes a nice video of the trip.

Continue reading “Cheap Muon Detectors Go Aloft On High-Altitude Balloon Mission”