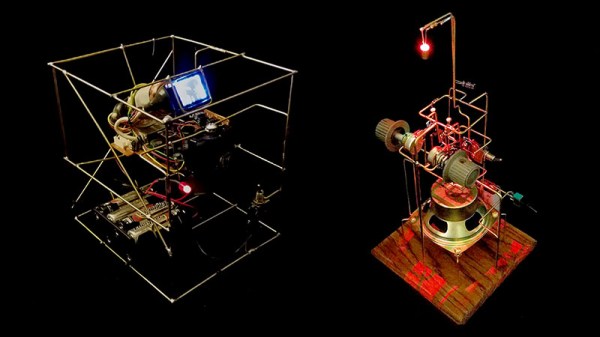

Sometimes a beautiful project is worth writing on that merit alone, but when it functions as designed,someone takes the time to create a thorough and beautiful landing page for their project, we get weak in the knees. We feel the need to grab the internet and point our finger for everyone to see. This is one of those projects that checks all our boxes. [Nathan Petersen] made a POV toy top called Razzler, jumping through every prototyping hoop along the way. The documentation he kept is what captured our hearts.

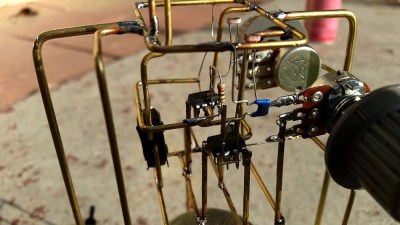

The project is a spinning top with an integrated persistence-of-vision (POV) display. That’s the line of LEDs that you see here. To sync up the patterns, the board includes an IMU, but detecting angular velocity with either gyroscope or accelerometer proved problematic. [Nathan’s] writeup of this is worth the read itself, but you’ll also enjoy the CNC workworking part of the project used to create the body of the spinning top.

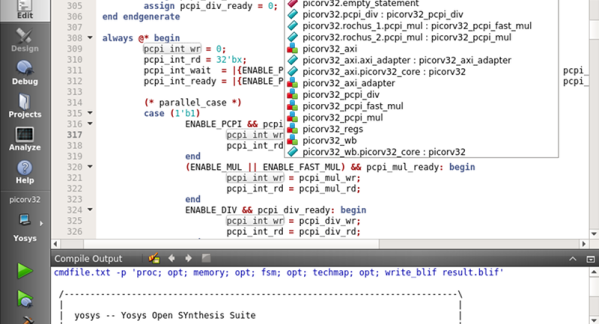

This was [Nathan]’s first big solo project, and so many of the steps are explained by someone who just entered the deep-end very quickly. If you have experience, you may grin at the simplified reasonings, but for a novice, it makes for an approachable lesson. The way he selects hardware and firmware is pragmatic and perhaps even overkill, so you know he’s going into engineering. This overshot saved him when there were communication problems which needed a sacrifice of some processing power to run I2C on some GPIO.

We hope you enjoy reading about this combinations of POV, firmware (or is it?), and centrifugal force.