[Peter] is at it again. Not content with being one of the best RC confabulators on YouTube, and certainly not content with the first airplane he built in his basement, [Peter Sripol] is building another airplane in his basement.

The first airplane he built was documented on YouTube over a month and a half. It was an all-electric biplane, built from insulation foam covered in fiberglass, and powered by a pair of ludicrously oversized motors usually meant for large-scale RC aircraft. This was built under Part 103 regulations — an ultralight — which means there were in effect no regulations. Anyone could climb inside one of these without a license and fly it. The plane flew, but there were a few problems. It was too fast, and the battery life wasn’t really what [Peter] wanted.

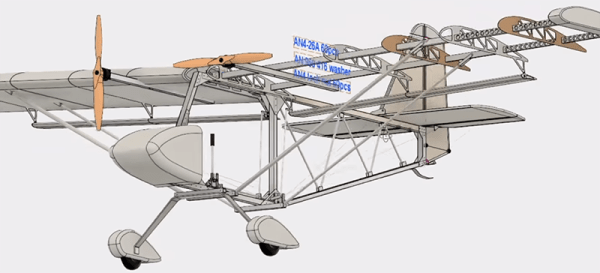

Now [Peter] is onto his next adventure. Compared to the previous plane, this has a more simplified, traditional construction. It’s a high wing monoplane with an aluminum frame. There are two motors again, although he’s still in the process of finding lower kV motors. This plane should also fly slower, longer, something you really want in an ultralight.

Now [Peter] is onto his next adventure. Compared to the previous plane, this has a more simplified, traditional construction. It’s a high wing monoplane with an aluminum frame. There are two motors again, although he’s still in the process of finding lower kV motors. This plane should also fly slower, longer, something you really want in an ultralight.

As far as tools required for this build, it’s surprising how few are needed to put the plane together. Of course, there are a few excessively large pop rivet guns and there will be some extra special aviation-grade bolts, but the majority of this plane will be made out of standard aluminum, insulation foam, a bit of wood, and some fiberglass. Watching [Peter] churn out high-end fabrication with these simple parts is so satisfying. If you have a drill press with a cross slide vise, you too can build a plane in your basement.

This is shaping up to be a truly fantastic build. [Peter] has already proven that yes, he can indeed build an airplane in his basement. This time, though, he’s going to have a plane that will stay in the air for more than just a few minutes.

Continue reading “Building An Ultralight In A Basement Is Just So Beautiful To See”