When a new piece of technology comes out, the price is generally so high that it keeps away everyone but the die hard early adopters. But with time the prices inch down enough that more people are willing to buy, which then drives the prices down even more, until eventually the economies of scale really kick in and the thing is so cheap that it’s almost an impulse buy. Linux SBCs, Blu-ray lasers, 3D printers; you name it and the hacker community has probably benefited from the fact that it’s not just the hacker community that’s interested anymore.

Which is exactly what’s started to happen with laser rangefinders. Once almost exclusively a military technology, you can now pick a basic “laser tape measure” for less than $40 USD from the normal overseas suppliers. Unfortunately, as [iliasam] found, they aren’t particularly well suited other tasks. For one there’s no official way of getting the data out of the thing, but the other problem is that the sample rate is less than one per second. Believing the hardware itself was promising enough, he set out to reverse engineer and replace the firmware running on one of these cheap laser rangefinders (Google Translate from Russian).

His blog post is an absolute wealth of information on how these devices operate, and a must read for anyone interested in reverse engineering. But the short version is that he figured out a way to reprogram the STM32F100C8T6 microcontroller used in the device, and develop his own firmware that addresses the usability concerns of this otherwise very promising gadget.

His blog post is an absolute wealth of information on how these devices operate, and a must read for anyone interested in reverse engineering. But the short version is that he figured out a way to reprogram the STM32F100C8T6 microcontroller used in the device, and develop his own firmware that addresses the usability concerns of this otherwise very promising gadget.

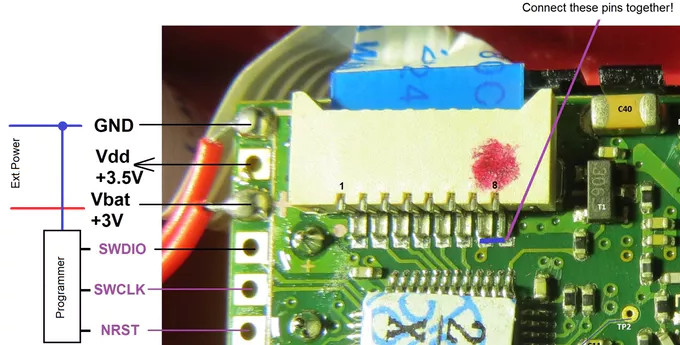

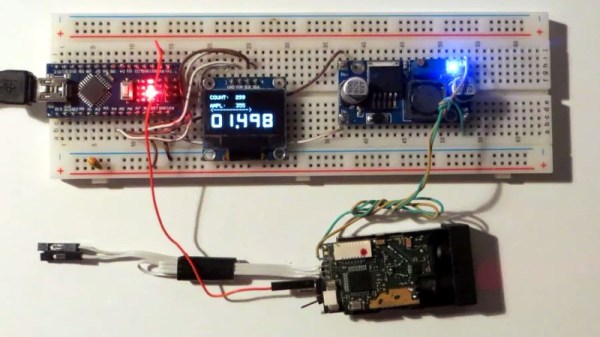

With some minor hoop jumping, the laser tape measure PCB can be hooked up to an ST-Link programmer, and the firmware provided by [iliasam] can be used to enable an easy to use serial interface. Perfect for pairing with an Arduino or Raspberry Pi to get fast and accurate range data without breaking the bank.

It probably won’t surprise you to see this isn’t the first time [iliasam] has gotten down and dirty with a laser rangefinder. This extremely impressive build from last year allowed for incredibly accurate 3D scans of his room, and before that he created his own rangefinder from scratch.

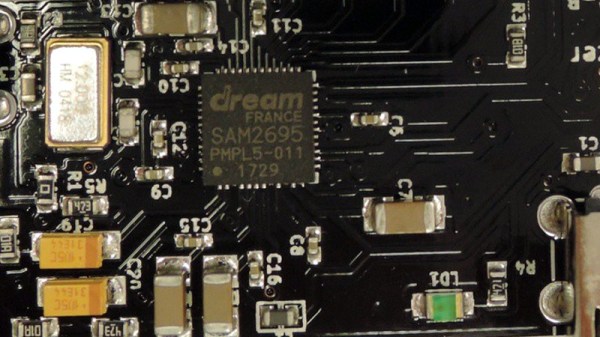

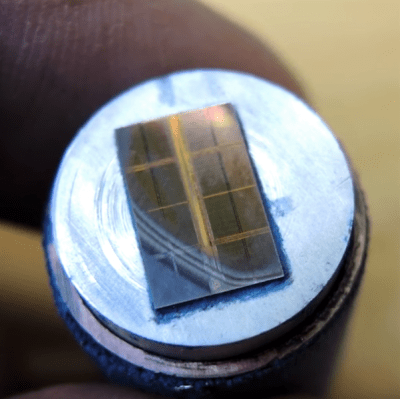

For those not into the anatomy and physiology of semiconductors, getting a look at the inside of the chip can reveal valuable information needed to reverse engineer a device, or it can just scratch the itch of curiosity. Lapping (the gentle grinding away of material) is one way to see the layers that make up the silicon die that lies beneath the epoxy. Hard drives designed to spin at 7200 rpm or more hardly seem a suitable spinning surface for a gentle lapping, but [electronupdate] just wanted the platter for its ultra-smooth, ultra-flat surface.

For those not into the anatomy and physiology of semiconductors, getting a look at the inside of the chip can reveal valuable information needed to reverse engineer a device, or it can just scratch the itch of curiosity. Lapping (the gentle grinding away of material) is one way to see the layers that make up the silicon die that lies beneath the epoxy. Hard drives designed to spin at 7200 rpm or more hardly seem a suitable spinning surface for a gentle lapping, but [electronupdate] just wanted the platter for its ultra-smooth, ultra-flat surface.