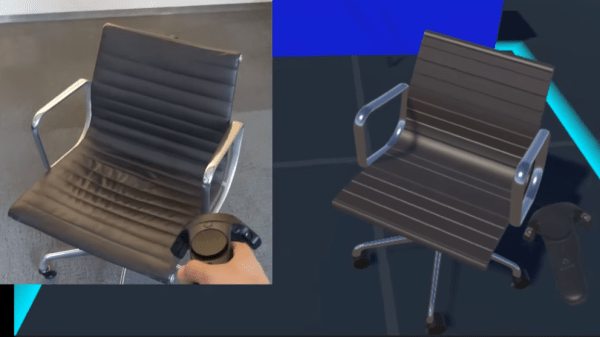

This video demonstrates a really interesting experiment: sticking a Vive Tracker onto an ordinary chair in order to sync it up perfectly with its VR counterpart. The result? A chair that is visible in VR as a virtual object, but has a 1:1 physical world version occupying the same space. This means that unlike any other virtual object, this chair can be seen, touched, felt, moved, and actually sat in while the user is immersed in VR.

The purpose of this experiment seems to have been to virtually explore seating arrangements for real-world environments, and spawned a theatre planning tool by design studio [Agile Lens]. But we wonder if there’s unrealized potential in the idea of connecting physical objects that can be touched and held (or sat on) with their VR counterparts. Video demos of the chair test are embedded below.