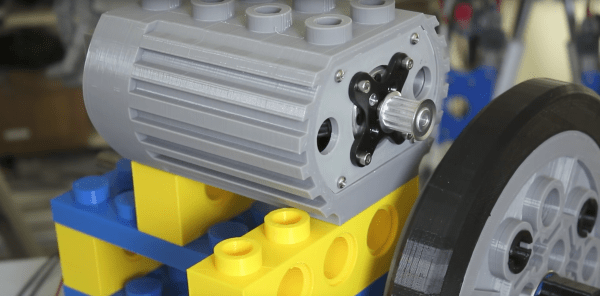

A few months ago, [Tom] built a few RC planes. The first was completely 3D printed, but the resulting print — and plane — came in a bit overweight, making it a terrible plane. The second plane was a VTOL tilt rotor, using aluminum box section for the wing spar. This plane was a lot of fun to fly, but again, a bit overweight and the airfoil was never quite right.

Obviously, there are improvements to be made in the field of 3D printed aeronautics, and [Tom]’s recent experiments with 3D printed ribs hit it out of the park.

If you’re unfamiliar, a wing spar is a very long member that goes from wingtip to wingtip, or from the fuselage to each wingtip, and effectively supports the entire weight of the plane. The ribs run perpendicular to the spar and provide support for the wing covering, whether it’s aluminum, foam board, or monokote.

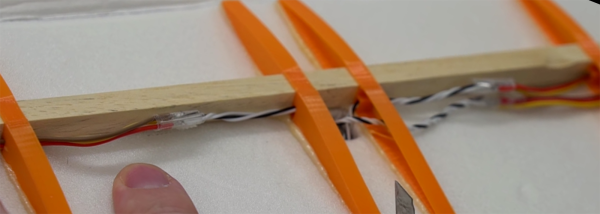

For this build, [Tom] is relying on the old standby, a square piece of balsa. The ribs, though, are 3D printed. They’re basically a single-wall vase in the shape of a wing rib, and are attached to the covering (foam board) with Gorilla glue.

Did the 3D printed ribs work? Yes, of course, you can strap a motor to a toaster and get it to fly. What’s interesting here is how good the resulting wing looked. It’s not quite up to the quality of fancy fiberglass wings, but it’s on par with any other foam board construction.

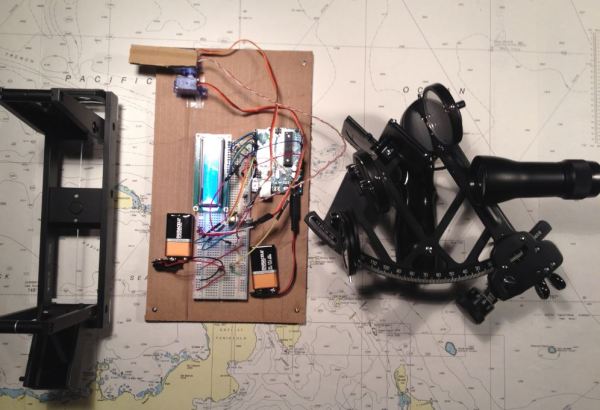

The takeaway, though, is how much lighter this construction was when compared to the completely 3D printed plane. With similar electronics, the plane with the 3D printed ribs weighed in at 312 grams. The completely 3D printed plane was a hefty 468 grams. That’s a lot of weight saved, and that translates into more flying time.

You can check out the build video below.

Continue reading “3D Printed Ribs For Not 3D Printed Planes”