You’ll all be familiar with the PC, the ubiquitous x86-powered workhorse of desktop and portable computing. All modern PCs are descendants of the original from IBM, the model 5150 which made its debut in August 1981. This 8088-CPU-driven machine was expensive and arguably not as accomplished as its competitors, yet became an instant commercial success.

The genesis of its principal operating system is famous in providing the foundation of Microsoft’s huge success. They had bought Seattle Computer Products’ 86-DOS, which they then fashioned into the first release version of IBM’s PC-DOS. And for those interested in these early PC operating systems there is a new insight to be found, in the form of a pre-release version of PC-DOS 1.0 that has found its way into the hands of OS/2 Museum.

Sadly they don’t show us the diskette itself, but we are told it is the single-sided 160K 5.25″ variety that would have been the standard on these early PCs. We say “the standard” rather than “standard” because a floppy drive was an optional extra on a 5150, the most basic model would have used cassette tape as a storage medium.

The disk is bootable, and indeed we can all have a play with its contents due to the magic of emulation. The dates on the files reveal a date of June 1981, so this is definitely a pre-release version and several months older than the previous oldest known PC-DOS version. They detail an array of differences between this disk and the DOS we might recognise, perhaps the most surprising of which is that even at this late stage it lacks support for .EXE executables.

You will probably never choose to run this DOS version on your PC, but it is an extremely interesting and important missing link between surviving 86-DOS and PC-DOS versions. It also has the interesting feature of being the oldest so-far-found operating system created specifically for the PC.

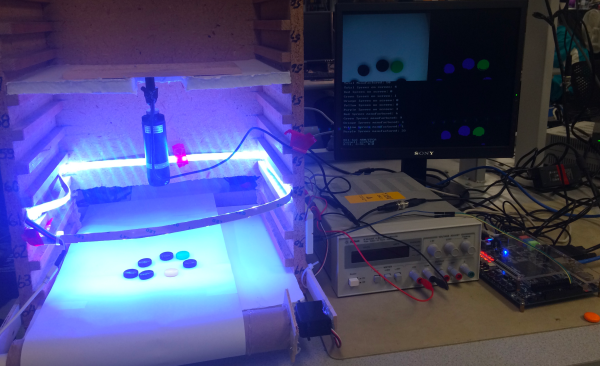

If you are interested in early PC hardware, take a look at this project using an AVR processor to emulate a PC’s 8088.

Header image: (CC BY-SA 3.0 DE).