With more and more cars driving themselves, there is an increasing demand for precise environment aware sensors. From collision avoidance to smooth driving, environmental awareness is a must have for any self-driving cars. Enter automotive radar: cool, precise and relatively cheap. Thanks to a donated automotive radar module, [Shahriar] gifts us with a “tutorial, experiment and teardown.”

Before digging into the PCB, [Shahriar] explains the theory. With just enough math for the mathmagically inclined and not too much for the math adverse, [Shahriar] goes into the details of how automotive radar is different from normal stationary radar.

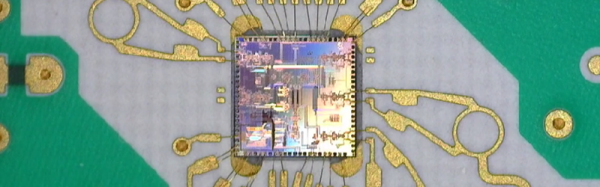

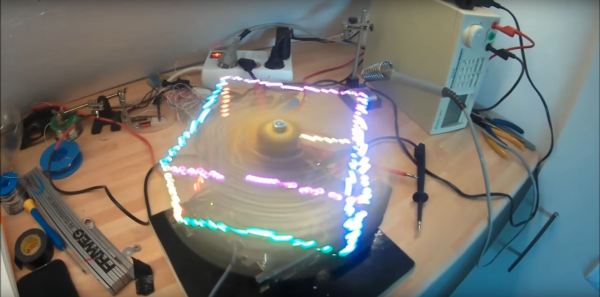

Only after a brief overview of the Doppler effect, [Shahriar] digs into the PCB which reveals three die-on-PCB ASICs responsible for generating and receiving 77GHz FMCW signals coupled to a 2D array of antennas. Moreover, [Shahriar] points out the several microwave components such as “rat-race couplers” and “branchline couplers.” Additionally, [Shahriar] shows off his cool PCB rulers from SV1AFN Design Lab that he uses as a reference for these microwave components. Finally, a physical embodiment of the Doppler effect radar is demonstrated with a pair of Vivaldi horn antennas and a copper sheet.

We really like how [Shahriar] structures his video: theory, followed by a teardown and then a physical experiment to drive his lesson home. If he didn’t already have a job, we’d say he might want to consider teaching. If the video after the break isn’t enough radar for the day, we’ve got you covered.