If you’re dealing with RF, you’ll probably have the need to generate a variety of clock signals. Fortunately, [Jason] has applied his knowledge to build a SI5351 library for the Arduino and a breakout board for the chip.

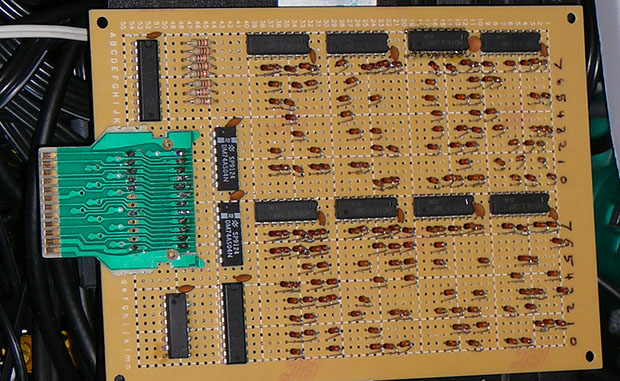

The SI5351 is a programmable clock generator. It can output up to eight unique frequencies at 8 kHz to 133 MHz. This makes it a handy tool for building up RF projects. [Jason]’s breakout board provides 3 isolated clock outputs on SMA connectors. A header connects to an Arduino, which provides power and control over I2C.

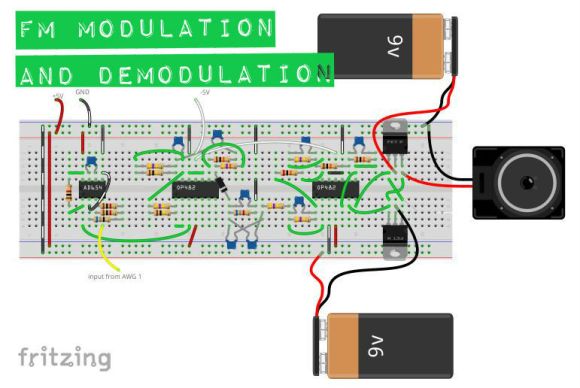

If you’re looking for an application, [Jason]’s prototype single-sideband radio shows the chip in action. This radio uses two of the SI5351 clocks: one for the VFO and one for the BFO. This reduces the part count, and could make this design quite cheap.

The Arduino library is available on Github, and you can order a SI5351 breakout board from OSHPark.

Last week we rolled out

Last week we rolled out