When it comes to LEGO and sorting, the idea is usually to sort bricks by color, which is a great way to help keep your sanity. And if you want to buy more, you may need to save your pennies and so on. What better way for worlds to collide than to build a working LEGO coin sorter?

[brickstudios]’ sorter does it all — pennies, nickels, dimes, quarters, half-dollars, and dollars. As with most coin sorters, the idea is to differentiate by size. This brings up challenge number one — the fact that a penny is ever-so-slightly bigger than a dime.

[brickstudios]’ sorter does it all — pennies, nickels, dimes, quarters, half-dollars, and dollars. As with most coin sorters, the idea is to differentiate by size. This brings up challenge number one — the fact that a penny is ever-so-slightly bigger than a dime.

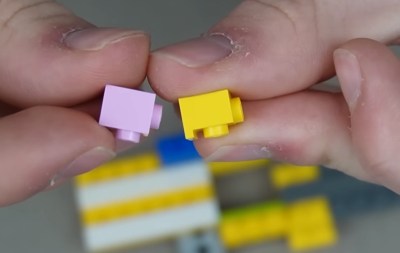

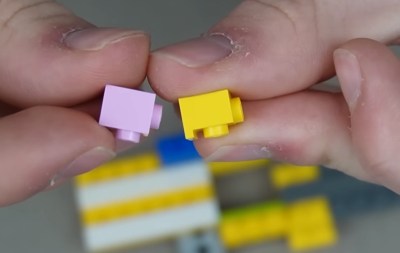

[brickstudios] was able to solve this by leveraging the difference between a headlight brick and a regular modified 1X1 with a stud on the side. Later, the same two coins reveal challenge two, which is that if you want to sort the coins in order by value, you have to somehow get the dimes past the pennies and nickels after each has fallen through the chute. Same deal with the giant half-dollar and smaller dollar coins.

The basic sub-build is a pair of tile rails on which the coins slide and either fall into the hole or keep going based on value. Once [brickstudios] had all the coins falling just right, it was time to address the value vs. size issue. Essentially, they solved this by building a ramp that turns the dimes and dollars and gets them to the right spots. Be sure to check out the build video after the break.

We are constantly amazed by the things people can make out of LEGO, like this hydroelectric dam or this hydraulic excavator. Have you made something amazing? Let us know!

Continue reading “LEGO Coin Sorter Is So Money” →