The EDUC-8, a DIY minicomputer design that came out in “Electronics Australia” magazine, was almost the world’s first in August 1974. And it would have been tied for the world’s first if inventor [Jamieson “Jim” Rowe] hadn’t held back from publishing to rework the design to expand the memory to a full 256 bytes. The price of perfectionism?

Flash forward 50 years, and [Gwyllym Suter] has taken on the job of recreating the EDUC-8 using modern PCBs, but otherwise staying true to the all-TTL design. He has all of his schematics up on the project’s GitHub, but has also sent us a number of beauty shots that we’re including below. Other than the progress of PCB tech and the very nice 3D-printed housing, they look identical. We have to admit that we love those wavy hand-drawn traces on the original, but we wouldn’t be sad about not having to solder in all those jumpers.

Continue reading “The World’s First DIY Minicomputer Was Almost Australian”

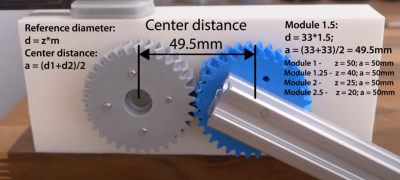

durability and increase noise. On the other hand, helical gears have a more gradual engagement, resulting in reduced noise and smoother operation. This leads to an increased load-carrying capacity, thus improving durability and lifespan.

durability and increase noise. On the other hand, helical gears have a more gradual engagement, resulting in reduced noise and smoother operation. This leads to an increased load-carrying capacity, thus improving durability and lifespan.