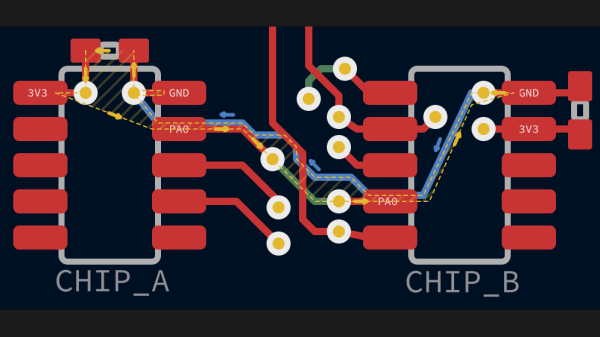

Here’s a question for you: when your PCB has a ground plane layer, where do return signals flow? It seems like a trick question, but as [Kristof Mulier] explains, there’s more to return path routing (alternate link in case you run into a paywall) than just doing a copper pour and calling it a day.

Like so many other things in life, the answer to the above question is “it depends,” and as [Kristof] ably demonstrates in this concise article, the return path for a signal largely depends on its frequency. He begins by explaining current loop areas and how they factor into the tendency for a circuit to both emit and be susceptible to electromagnetic noise. The bigger the loop area, the worse things can get from a noise perspective. At low frequencies, return signals will tend to take the shortest possible path, which can result in large current loop areas if you’re not careful. At higher frequencies, though, signals will tend to follow the path of minimal energy instead, which generally ends up being similar to the signal trace, even if it has a huge ground plane to flow through.

Since high-frequency signals naturally follow a path through the ground plane that minimizes the current loop, that means the problem takes care of itself, right? It would, except that we have a habit of putting all kinds of gaps in the way, from ground plane vias to isolation slots. [Kristof] argues that this can result in return paths that wiggle around these features, increasing the current loop area to the point where problems creep in. His solution? Route all your signal return paths. Even if you know that the return traces are going to get incorporated into a pour, the act of intentionally routing them will help minimize the current loop area. It’s brilliantly counterintuitive.

This is the first time we’ve seen the topic of high-frequency return paths tackled. This succinct demonstration shows exactly how return path obstructions can cause unexpected results.

Thanks to [Marius Heier] for the tip.

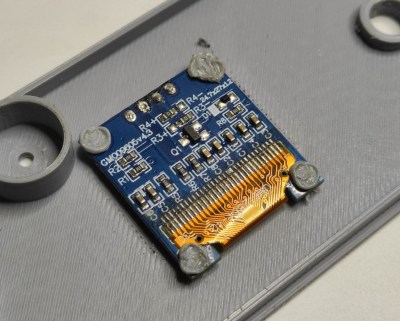

Whether you want to play alone or with a friend, it’s a classic to have in your pocket for sure. The brains behind this 70s-era operation is a Seeed Xiao ESP32-C3, which takes input from the two potentiometers and outputs the game on a 128 x 64 OLED. There’s also a small buzzer for when the ball hits the paddle, or you or your friend slips one past the goalie.

Whether you want to play alone or with a friend, it’s a classic to have in your pocket for sure. The brains behind this 70s-era operation is a Seeed Xiao ESP32-C3, which takes input from the two potentiometers and outputs the game on a 128 x 64 OLED. There’s also a small buzzer for when the ball hits the paddle, or you or your friend slips one past the goalie.