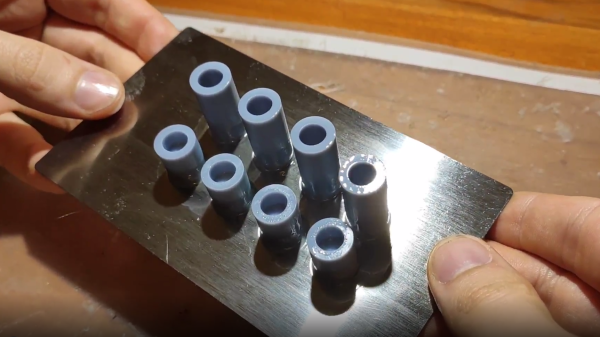

Despite the impressive variety of thermoplastics that can be printed on consumer-level desktop 3D printers, the most commonly used filament is polylactic acid (PLA). That’s because it’s not only the cheapest material available, but also the easiest to work with. PLA can be extruded at temperatures as low as 180 °C, and it’s possible to get good results even without a heated bed. The downside is that objects printed in PLA tend to be somewhat brittle and have a low heat tolerance. It’s a fine plastic for prototyping and light duty projects, but it won’t take long for many users to outgrow its capabilities.

The next step up is usually polyethylene terephthalate glycol (PETG). This material isn’t much more difficult to work with than PLA, but is more durable, can handle higher temperatures, and in general is better suited for mechanical parts. If you need greater durability or higher heat tolerance than PETG offers, you could move on to something like acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), polycarbonate (PC), or nylon. But this is where things start to get tricky. Not only are the extrusion temperatures of these materials greater than 250 °C, but an enclosed print chamber is generally recommended for best results. That puts them on the upper end of what the hobbyist community is generally capable of working with.

But high-end industrial 3D printers can use even stronger plastics such as polyetherimide (PEI) or members of the polyaryletherketone family (PAEK, PEEK, PEKK). Parts made from these materials are especially desirable for aerospace applications, as they can replace metal components while being substantially lighter.

These plastics must be extruded at temperatures approaching 400 °C, and a sealed build chamber kept at >100 °C for the duration of the print is an absolute necessity. The purchase price for a commercial printer with these capabilities is in the tens of thousands even on the low end, with some models priced well into the six figure range.

Of course there was a time, not quite so long ago, where the same could have been said of 3D printers in general. Machines that were once the sole domain of exceptionally well funded R&D labs now sit on the workbenches of hackers and makers all over the world. While it’s hard to say if we’ll see the same race to the bottom for high temperature 3D printers, the first steps towards democratizing the technology are already being made.

Continue reading “Bringing High Temperature 3D Printing To The Masses”