The Etch-a-Sketch was a popular toy, but a polarizing one. You were either one of those kids that had the knack, or one of the kids that didn’t. [Micah] was pretty firmly in the latter group, so decided to roboticize the Etch-a-Sketch so a computer could draw for him instead.

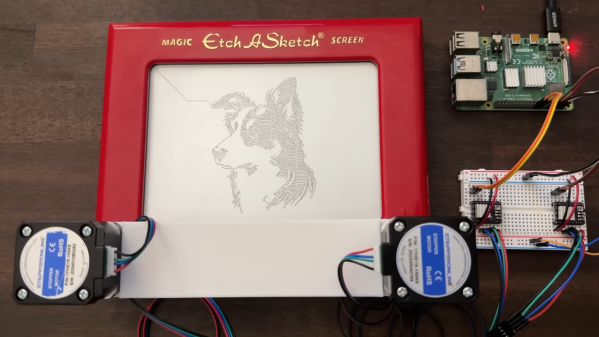

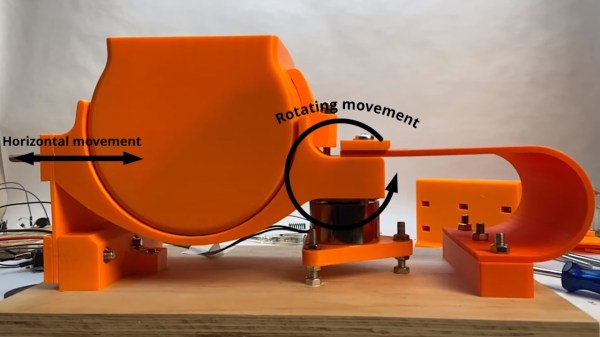

The build uses a pair of stepper motors attached to the Etch-a-Sketch’s knobs via 3D-printed adapters. It took [Micah] a few revisions to get the right design and the right motors for the job, but it all came together. A Raspberry Pi is charged with driving the motors to draw the desired picture.

Beyond the mechanics, [Micah] also does a great job of explaining the challenges around drawing and the drive software. Namely, the Etch-a-Sketch has a major limitation in that there’s no way to move the stylus without drawing a line. He accounts for this in his code for converting and drawing images.

The robot draws slowly but surely. The final result is incredibly impressive, and far exceeds what most of us could achieve on by hand. We’ve seen some similar builds in the past, too. Video after the break.