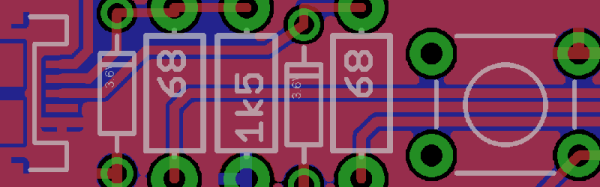

For the first in a series of posts describing how to make a PCB, we’re going with Eagle. Eagle CAD has been around since the days of DOS, and has received numerous updates over the years. Until KiCad started getting good a few years ago, Eagle CAD was the de facto standard PCB design software for hobbyist projects. Sparkfun uses it, Adafruit uses it, and Dangerous Prototypes uses it. The reason for Eagle’s dominance in a market where people don’t want to pay for software is the free, non-commercial and educational licenses. These free licenses give you the ability to build a board big enough and complex enough for 90% of hobbyist projects.

Of course, it should be mentioned that Eagle was recently acquired by Autodesk. The free licenses will remain, and right now, it seems obvious Eagle will become Autodesk’s pro-level circuit and board design software.

Personally, I learned PCB design on Eagle. After a few years, I quickly learned how limited even the professional version of Eagle was. At that point, the only option was to learn KiCad. Now that Eagle is in the hands of Autodesk, and I am very confident Eagle is about to get really, really good, I no longer have the desire to learn KiCad.

With the introduction out of the way, let’s get down to making a PCB in Eagle.

Continue reading “Creating A PCB In Everything: Eagle, Part 1”