Over the last year it’s fair to say that a chill wind has blown across the face of the media industry, as the prospect emerges that many content creation tasks formerly performed by humans instead being swallowed up by the inexorable rise of generative AI. In a few years we’re told, there may even be no more journalists, as the computers become capable of keeping your news desires sated with the help of their algorithms.

Here at Hackaday, we can see this might be the case for a gutter rag obsessed with celebrity love affairs and whichever vegetable is supposed to cure cancer this week, but we continue to believe that for quality coverage of the latest and greatest in the hardware hacking world, you can’t beat a writer made of good old-fashioned meat. Indeed, in a world saturated by low-quality content, the opinions of smart and engaged writers become even more valuable. So we’ve decided to go against the trend, by launching not a journalist powered by AI, but an AI powered by journalists.

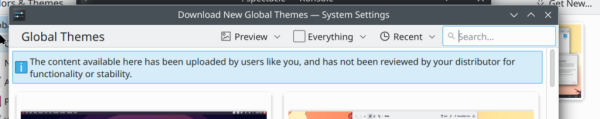

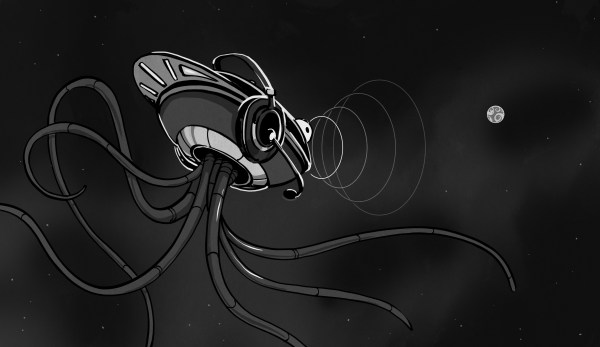

Announcing Wrencher-2, a Hackaday chat assistant in your browser

Wrencher-2 is a new paradigm in online chat assistants, eschewing generative algorithms in favour of the collective expertise of the Hackaday team. Ask Wrencher-2 a question, and you won’t get a vague and made-up answer from a computer, instead you’ll get a pithy and on-the-nail answer from a Hackaday staffer. Go on – try it! Continue reading “Wrencher-2: A Bold New Direction For Hackaday”