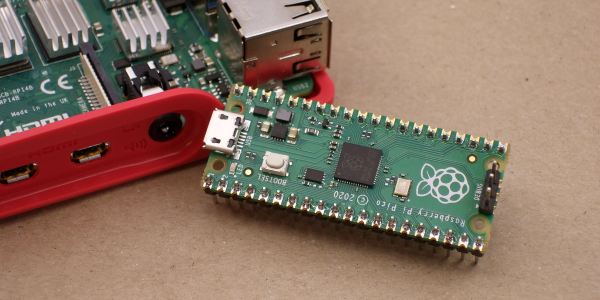

Raspberry Pi was synonymous with single-board Linux computers. No longer. The $4 Raspberry Pi Pico board is their attempt to break into the crowded microcontroller module market.

The microcontroller in question, the RP2040, is also Raspberry Pi’s first foray into custom silicon, and it’s got a dual-core Cortex M0+ with luxurious amounts of SRAM and some very interesting custom I/O peripheral hardware that will likely mean that you never have to bit-bang again. But a bare microcontroller is no fun without a dev board, and the Raspberry Pi Pico adds 2 MB of flash, USB connectivity, and nice power management.

As with the Raspberry Pi Linux machines, the emphasis is on getting you up and running quickly, and there is copious documentation: from “Getting Started” type guides for both the C/C++ and MicroPython SDKs with code examples, to serious datasheets for the Pico and the RP2040 itself, to hardware design notes and KiCAD breakout boards, and even the contents of the on-board Boot ROM. The Pico seems designed to make a friendly introduction to microcontrollers using MicroPython, but there’s enough guidance available for you to go as deep down the rabbit hole as you’d like.

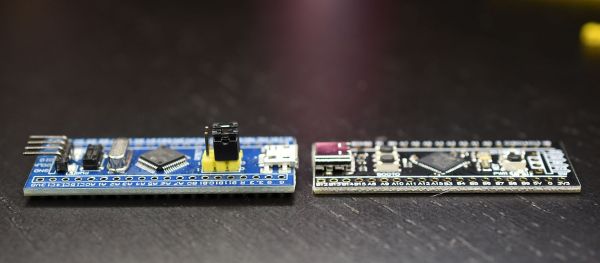

Our quick take: the RP2040 is a very well thought-out microcontroller, with myriad nice design touches throughout, enough power to get most jobs done, and an innovative and very hacker-friendly software-defined hardware I/O peripheral. It’s backed by good documentation and many working examples, and at the end of the day it runs a pair of familiar ARM MO+ CPU cores. If this hits the shelves at the proposed $4 price, we can see it becoming the go-to board for many projects that don’t require wireless connectivity.

But you want more detail, right? Read on.

Continue reading “Raspberry Pi Enters Microcontroller Game With $4 Pico” →