The Game Genie is a classic of the early 90s video game scene. It’s how you would have beaten the Ninja Turtles game, and it’s why the connector in your NES doesn’t work as it should. They never made a Game Genie for the Atari 2600, though, because by the time the Game Genie was released, the Atari was languishing on the bottom shelves of Toys R Us. Now though, we have FPGAs and development tools. We can build our own. That’s exactly what [Andy] did, and his Game Genie for the 2600 works as well as any commercial product you’d find for this beleaguered console.

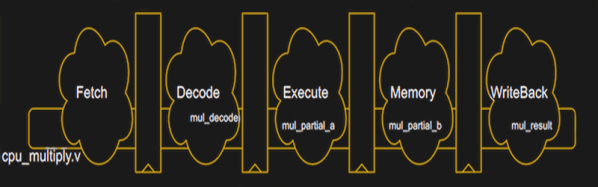

To understand how to build a Game Genie for an Atari, you first have to understand how a Game Genie works. The hacks for a Game Genie work by replacing a single byte in the ROM of a game. If your lives are stored at memory location 0xDEAD for example, you would just change that byte from 3 (the default) to 255 (because that’s infinite, or something). Combine this with 6-letter and 8-letter codes that denote which byte to change and what to change it to, and you have a Game Genie.

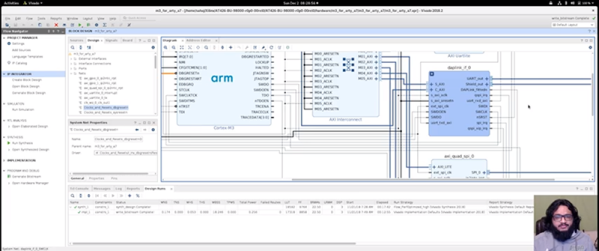

This build began by setting up a DE0 Nano FPGA development board to connect to an Atari 2600 cartridge. Yes, there are voltage level differences, but this can be handled with a few pin assignments. Then, it’s just a matter of writing Verilog to pass all the data from one set of address and data pins to another set of address and data pins. The FPGA becomes a man-in-the-middle attack, if you will.

This build began by setting up a DE0 Nano FPGA development board to connect to an Atari 2600 cartridge. Yes, there are voltage level differences, but this can be handled with a few pin assignments. Then, it’s just a matter of writing Verilog to pass all the data from one set of address and data pins to another set of address and data pins. The FPGA becomes a man-in-the-middle attack, if you will.

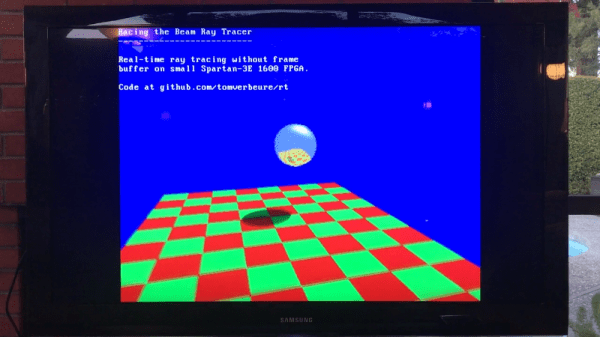

With the FPGA serving as a pass-through for the connections on the cartridge, it’s a simple matter to hard-code cheats into the device. For the example, [Andy] found the code for a game, figured out where the color of the fireballs were defined as red, and changed the color to blue. It worked, and all was right with the world. The work was then continued to create a user interface to enter three cheat codes, and finally wrapped up in a 3D printed enclosure. Sure, the Atari Game Genie works with ribbon cables, but it wouldn’t be that much more work to create a similar project with Lock-On™ technology. You can check out the entire build video below, or get the info over on Element14