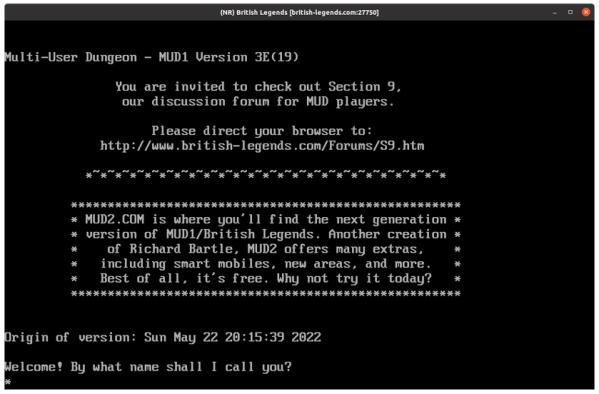

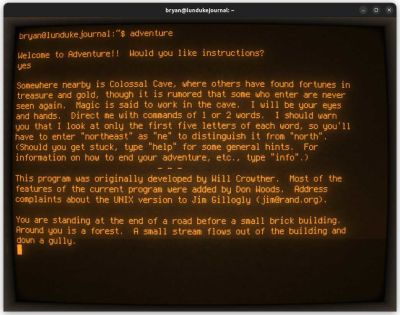

Born from a passion for caving and the wish to turn this into a digital adventure for all ages, Colossal Cave Adventure has grown from its quiet introduction in 1976 by William Crowther into the expanded game that inspired countless others to develop their own take on the genre, eventually leading to the realistically rendered graphical adventures we can play today. Yet even Colossal Cave Adventure has recently got a refresh in the form of a 3D graphical version, which has led [Bryan Lunduke] to take a look at how to best revisit the original text adventure.

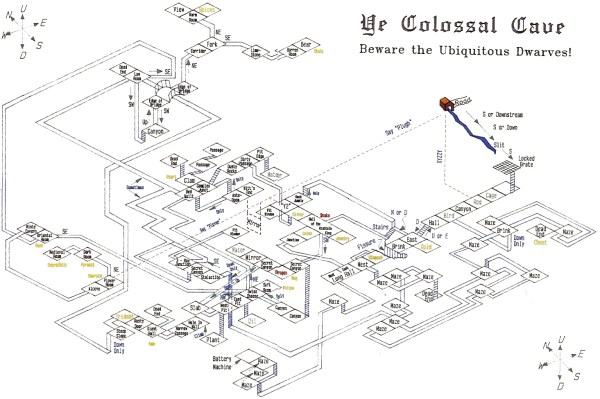

For those who are on Linux or a BSD system, the easiest way is to hop over to the package manager and install Colossal Cave Adventure straight away with the package bsdgames on Debian-based systems, or colossal-cave-adventure on others. A port by Eric S. Raymond of the 1995 version of the game can also be found as Open Adventure, and there’s a 1990-era DOS version you can experience on real hardware or even in a browser window, if that’s your thing. Or get it for your Amiga, Macintosh or OS/2. These days you can even get ready-to-use maps of the entire cave and surroundings, which along with walkthroughs can make things far too easy. Continue reading “The Many Ways To Play Colossal Cave Adventure After Nearly Half A Century”