Computer mice come in all kinds of shapes and sizes, but are typically designed to fit in the palm of your hand. While some users with large hands may find standard mice uncomfortably small, we don’t think anyone will ever make that complaint about the humongous peripheral [Felix Fisgus] made for a game called Office Job at the ENIAROF art festival in Marseille. With a length of about two meters we suspect it might be the largest functional computer mouse in existence.

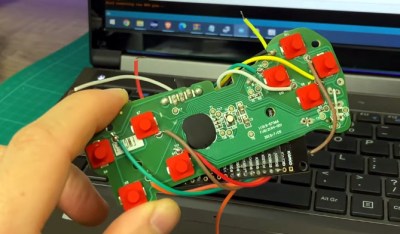

Inside the massive mouse is a wooden pallet with four caster wheels that enable smooth movement in all directions. This motion is detected by an ordinary optical mouse sensor: perhaps surprisingly, these can be used at this enormous scale simply by placing a different lens in front.

Inside the massive mouse is a wooden pallet with four caster wheels that enable smooth movement in all directions. This motion is detected by an ordinary optical mouse sensor: perhaps surprisingly, these can be used at this enormous scale simply by placing a different lens in front.

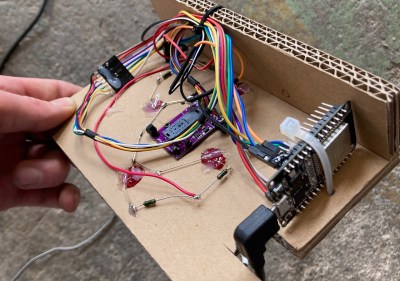

As for the mouse button, [Felix] and his colleagues found of that the bottom of an empty five-liter can has a nice “pop” to it and installed one in the front section of the device, hooked up to an ESP32 board that communicates with a computer through Bluetooth.

The mouse connects to an equally huge desktop computer, powered by a Raspberry Pi, on which users play a game that involves clicking on error messages from a wide variety of old and new operating systems. Moving the mouse and pressing its button to hit those dialog boxes is a two-person job, and turns the annoyance of software errors into a competitive game.

Optical mouse sensors are versatile devices: apart from their obvious purpose they can also serve as motion sensors for autonomous vehicles, or even as low-resolution cameras.

Continue reading “Massive Mouse Game Mimics Classic Software Crashes”