[Irene Posch] is big into knitted fabric circuits. And while most of the textile circuits that we’ve seen are content with simply conducting enough juice to light an LED, [Irene]’s sights are set on knittable crafted arithmetic logic units (ALUs). While we usually think of transistors as the fundamental building-blocks of logic circuits, [Irene] has developed what is essentially a knit crochet relay. Be sure to watch the video after the break to see it in construction and in action.

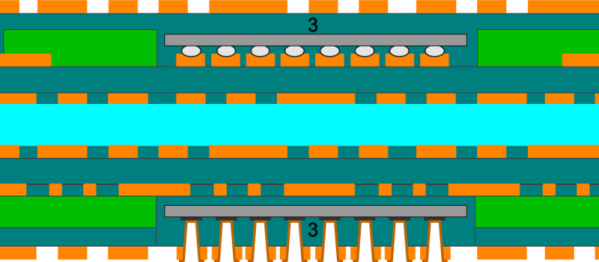

The basic construction is a coil of conductive thread that forms an electromagnet, and a magnetic bead suspended on an axle so that it can turn in response to the field. To create a relay, a flap of knit conductive thread is attached to the bead, which serves as the pole for what’s essentially a fabric-based SPDT switch. If you’ve been following any of our relay-logic posts, you’ll know that once you’ve got a relay, the next step to a functioning computer is a lot of repetition.

How does [Irene] plan to display the results of a computation? On knit-and-bead flipdot displays, naturally. Combining the same electromagnet and bead arrangement with beads that are painted white on one side and black on the other yields a human-readable one-bit display. We have an unnatural affinity for flipdot displays, and making the whole thing out of fabric-store components definitely flips our bits.

How does [Irene] plan to display the results of a computation? On knit-and-bead flipdot displays, naturally. Combining the same electromagnet and bead arrangement with beads that are painted white on one side and black on the other yields a human-readable one-bit display. We have an unnatural affinity for flipdot displays, and making the whole thing out of fabric-store components definitely flips our bits.

Anyway, [Irene Posch] is a textile-tech artist who you should definitely be following if you have any interest in knittable computers. Have you seen anything else like this? Thanks [Melissa] for the awesome tip!