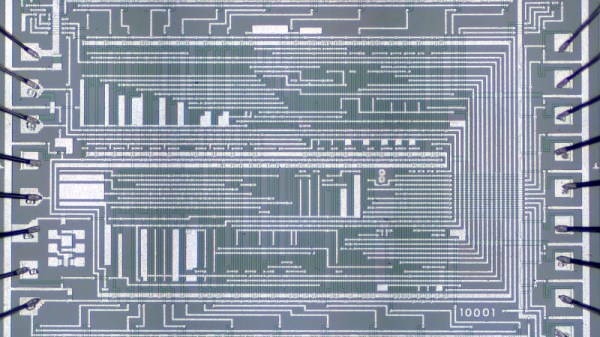

The history of storage devices is quite literally a race between the medium and the computing power as the bottleneck of preserving billions of ones and zeros stands in the way of computing nirvana. The most recent player is the Non-Volatile Memory Express (NVMe), something of a hybrid of what has come before.

The first generations of home computers used floppy disk and compact cassette-based storage, but gradually, larger and faster storage became important as personal computers grew in capabilities. By the 1990s hard drive-based storage had become commonplace, allowing many megabytes and ultimately gigabytes of data to be stored. This would drive up the need for a faster link between storage and the rest of the system, which up to that point had largely used the ATA interface in Programmed Input-Output (PIO) mode.

This led to the use of DMA-based transfers (UDMA interface, also called Ultra ATA and Parallel ATA), along with DMA-based SCSI interfaces over on the Apple and mostly server side of the computer fence. Ultimately Parallel ATA became Serial ATA (SATA) and Parallel SCSI became Serial Attached SCSI (SAS), with SATA being used primarily in laptops and desktop systems until the arrival of NVMe along with solid-state storage.

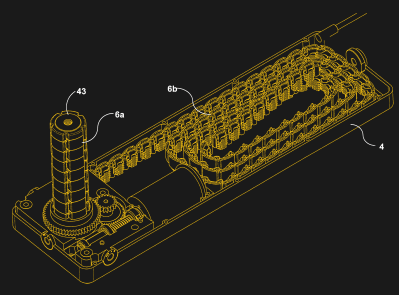

All of these interfaces were designed to keep up with the attached storage devices, yet NVMe is a bit of an odd duck considering the way it is integrated in the system. NVMe is also different for not being bound to a single interface or connector, which can be confusing. Who can keep M.2 and U.2 apart, let alone which protocol the interface speaks, be it SATA or NVMe?

Let’s take an in-depth look at the wonderful and wacky world of NVMe, shall we?

Continue reading “NVMe Blurs The Lines Between Memory And Storage”