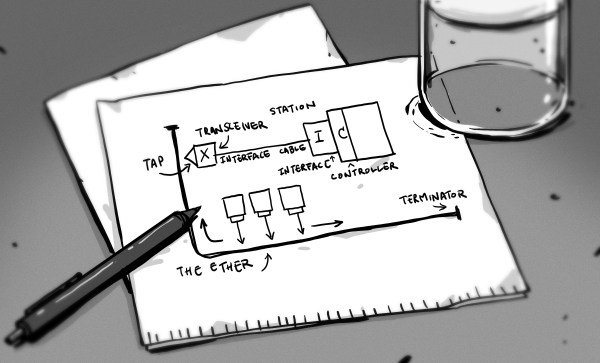

September 30th, 1980 is the day when Ethernet was first commercially introduced, making it exactly forty years ago this year. It was first defined in a patent filed by Xerox as a 10 Mb/s networking protocol in 1975, introduced to the market in 1980 and subsequently standardized in 1983 by the IEEE as IEEE 802.3. Over the next thirty-seven years, this standard would see numerous updates and revisions.

Included in the present Ethernet standard are not just the different speed grades from the original 10 Mbit/s to today’s maximum 400 Gb/s speeds, but also the countless changes to the core protocol to enable these ever higher data rates, not to mention new applications of Ethernet such as power delivery and backplane routing. The reliability and cost-effectiveness of Ethernet would result in the 1990 10BASE-T Ethernet standard (802.3i-1990) that gradually found itself implemented on desktop PCs.

With Ethernet these days being as present as the presumed luminiferous aether that it was named after, this seems like a good point to look at what made Ethernet so different from other solutions, and what changes it had to undergo to keep up with the demands of an ever-more interconnected world. Continue reading “Ethernet At 40: From A Napkin Sketch To Multi-Gigabit Links”