[Benjojo] got interested in where the magic number of 1,500 bytes came from, and shared some background on just how and why it seems to have come to be. In a nutshell, the maximum transmission unit (MTU) limits the maximum amount of data that can be transmitted in a single network-layer transaction, but 1,500 is kind of a strange number in binary. For the average Internet user, this under the hood stuff doesn’t really affect one’s ability to send data, but it has an impact from a network management point of view. Just where did this number come from, and why does it matter?

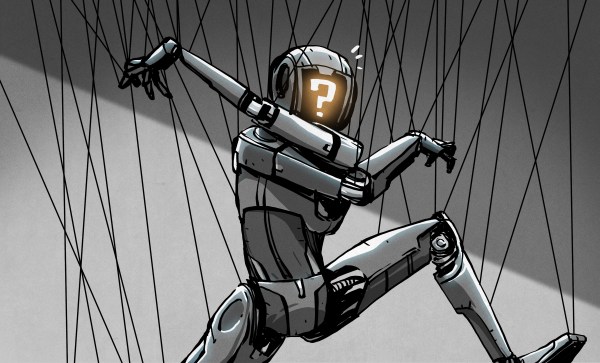

[Benjojo] looks at a year’s worth of data from a major Internet traffic exchange and shows, with the help of several graphs, that being stuck with a 1,500 byte MTU upper limit has real impact on modern network efficiency and bandwidth usage, because bandwidth spent on packet headers adds up rapidly when roughly 20% of all packets are topping out the 1,500 byte limit. Naturally, solutions exist to improve this situation, but elegant and effective solutions to the Internet’s legacy problems tend to require instant buy-in and cooperation from everyone at once, meaning they end up going in the general direction of nowhere.

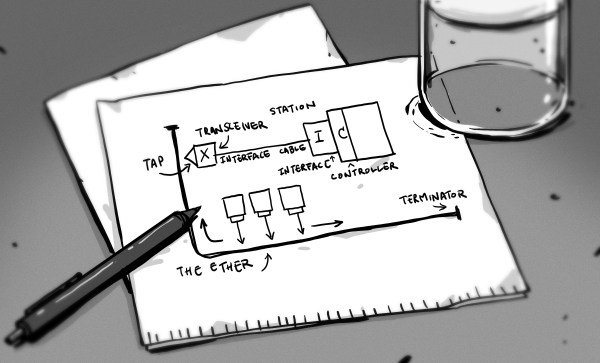

So where did 1,500 bytes come from? It appears that it is a legacy value originally derived from a combination of hardware limits and a need to choose a value that would play well on shared network segments, without causing too much transmission latency when busy and not bringing too much header overhead. But the picture is not entirely complete, and [Benjojo] asks that if you have any additional knowledge or insight about the 1,500 bytes decision, please share it because manuals, mailing list archives, and other context from that time is either disappearing fast or already entirely gone.

Knowledge fading from record and memory is absolutely a thing that happens, but occasionally things get saved instead of vanishing into the shadows. That’s how we got IGNITION! An Informal History of Liquid Rocket Propellants, which contains knowledge and history that would otherwise have simply disappeared.