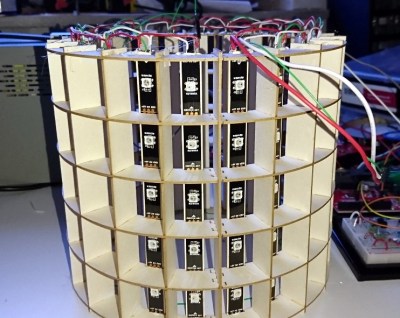

According to [makeTVee], his latest project started out as an experiment to see how well the LED matrix techniques he’s worked with in the past would translate to a cylindrical form factor. We’re going to go ahead and say that not only was the test a success, but that the concept definitely holds promise for displays that are both functional and aesthetically pleasing. This build stops a bit short of being a complete implementation, but what he has so far is very promising and we hope he continues fleshing it out.

A laser cutter was used to create the interlocking segments that make up the display’s frame, but we imagine you could pull off a similar design using 3D printed parts if you don’t have access to a laser. Strips of WS2812 LEDs are mounted along the inside of the cylinder so that each individual LED lines up with the center of a cell. To finish off the outside of the cylinder [makeTVee] used a thin wood veneer called MicroWOOD, which gives the LEDs a nice diffused glow. The wood grain in the veneer also provides an organic touch that keeps the whole thing from looking too sterile.

A laser cutter was used to create the interlocking segments that make up the display’s frame, but we imagine you could pull off a similar design using 3D printed parts if you don’t have access to a laser. Strips of WS2812 LEDs are mounted along the inside of the cylinder so that each individual LED lines up with the center of a cell. To finish off the outside of the cylinder [makeTVee] used a thin wood veneer called MicroWOOD, which gives the LEDs a nice diffused glow. The wood grain in the veneer also provides an organic touch that keeps the whole thing from looking too sterile.

Of course, a display like this only works if you’ve got software to drive it. To that end, [makeTVee] has used pygame to create a simulator on his computer that shows what the display would look like if it were unrolled and flattened it out. This makes it a lot easier to create content, as you can see the whole display at once. He says the source for the new tool will be coming to GitHub soon, and we’re very interested in taking a look.

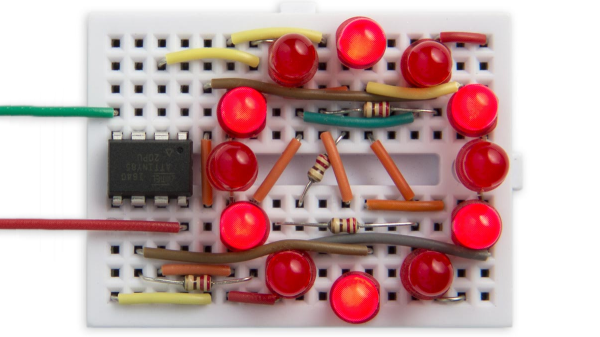

If this display looks familiar, it’s probably because a distinctly flatter version of it took the top spot in our “Visualize it with Pi” contest last year.

Continue reading “Cylindrical LED Display Comes Full Circle”