Heat Pumps are an extremely efficient way to maintain climate control in a building. Unlike traditional air conditioners, heat pumps can also effectively work in reverse to warm a home in winter as well as cool it in summer; with up to five times the efficiency of energy use as a traditional electric heater. Even with those tremendous gains in performance, there are still some ways to improve on them as [Martin] shows us with some modifications he made to his heat pump system.

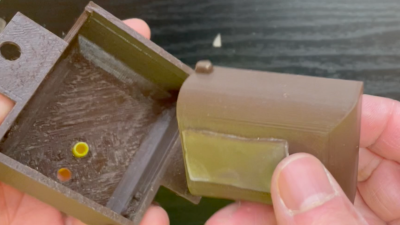

This specific heat pump is being employed not for climate control but for water heating, which sees similar improvements in efficiency over a standard water heater. The problem with [Martin]’s was that even then it was simply running much too often. After sleuthing the energy losses and trying a number of things including a one-way valve on the heating water plumbing to prevent siphoning, he eventually found that the heat pump was ramping up to maximum temperature once per day even if the water tank was already hot. By building a custom master controller for the heat pump which includes some timing relays, the heat pump only runs up to its maximum temperature once per week.

While there are some concerns with Legionnaire’s bacteria if the system is not maintained properly, this modification still meets all of Australia’s stringent building code requirements. His build is more of an investigative journey into a more complex piece of machinery, and his efforts net him a max energy usage of around 1 kWh per day which is 50% more efficient than it was when it was first installed. If you’re looking to investigate more into heat pumps, take a look at this DIY Arduino-controlled mini heat pump.

Continue reading “Custom Controller Ups Heat Pump Efficiency”