Do you need portable power that packs a punch? Sure you do, especially if you want to light up the night by mummifying yourself with a ton of LED strips. You aren’t limited to that, of course, but it’s what we pictured when we read about [Jeremy]’s Thunder Pack. With four PWM channels at 2.3 A each, why not go nuts? [Jeremy] has already proven the Thunder Pack out by putting it through its paces all week at Burning Man.

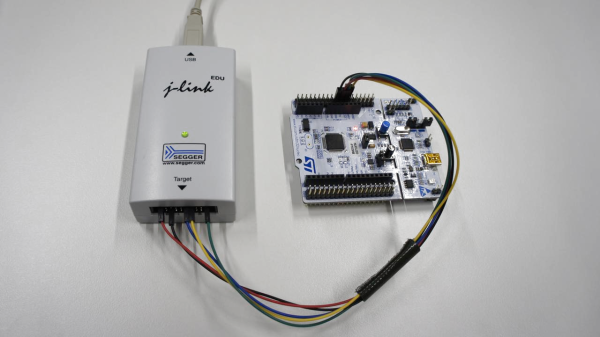

After a few iterations, [Jeremy] has landed on the STM32 microcontroller family and is currently working to upgrade to one with enough flash memory to run CircuitPython.

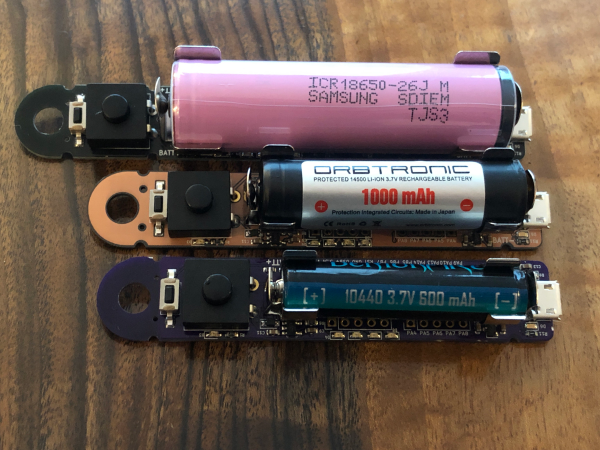

The original version was designed to run on a single 18650 cell, but [Jeremy] now has three boards that support similar but smaller rechargeable cells for projects that don’t need quite as much power.

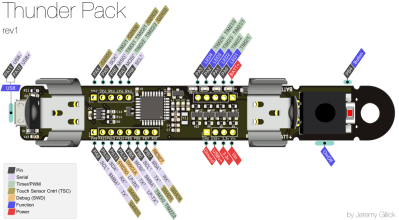

We love how small and powerful this is, and the dongle hole is a great touch because it opens up options for building it into a wearable. [Jeremy] made a fantastic pinout diagram and has a ton of code examples in the repo. If you want to wade into the waters of wearables, let whimsical wearables wizard [Angela Sheehan] walk you through the waves.

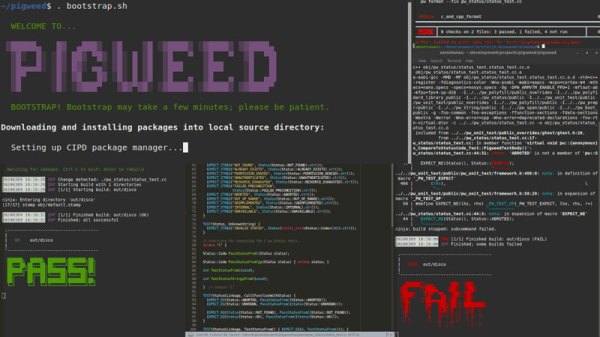

Google

Google