The modern hacker wields a number of tools that operate on the principle of heating things up to extremely high temperatures, so a smoke alarm is really a must-have piece of equipment. But in an era where it seems everything is getting smarter, some might wonder if even our safety gear could benefit from joining the Internet of Things. Interested in taking a crack at improving the classic smoke alarm, [Vivek Gupta] grabbed a NodeMCU and started writing some code.

Now before you jump down to the comments and start smashing that keyboard, let’s make our position on this abundantly clear. Do not try to build your own smoke alarm. Seriously. It takes a special kind of fool to trust their home and potentially their life to a $5 development board and some Arduino source code they copied and pasted from the Internet. That said, as a purely academic exercise it’s certainly worth examining how modern Internet-enabled microcontrollers can be used to add useful features to even the most mundane of household devices.

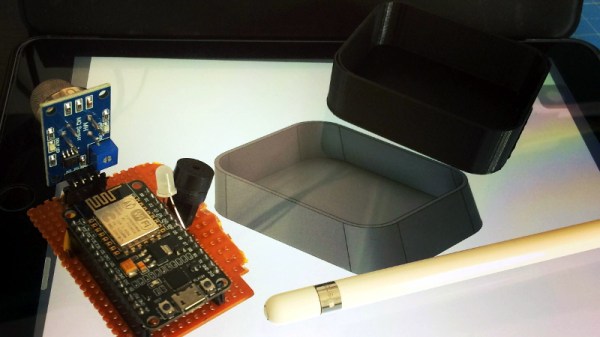

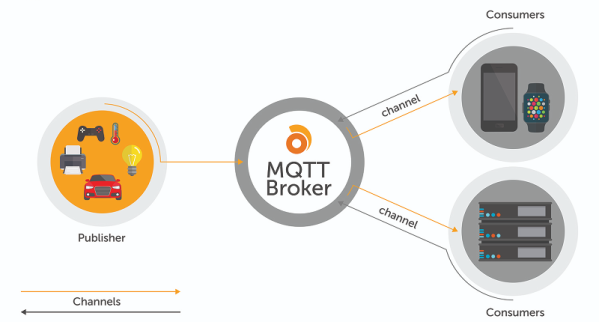

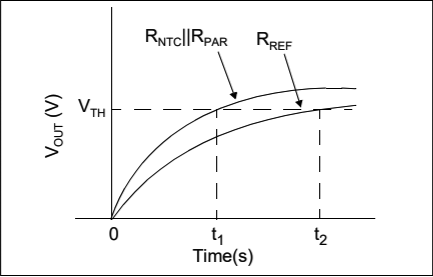

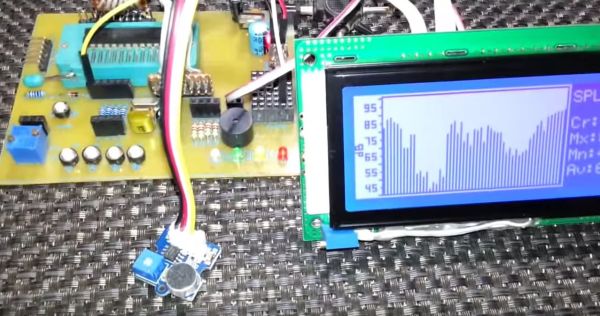

In this case, [Vivek] is experimenting with the idea of a smoke alarm that can be silenced through your home automation system in the event of a false alarm. He’s using Google Assistant and IFTTT, but the code could be adapted to whatever method you’re using internally to get all your gadgets on the same virtual page. On the hardware side of things, the test system is simply a NodeMCU connected to a buzzer and a MQ2 gas sensor.

So how does it work? If the detector goes off while [Vivek] is cooking, he can tell Google Assistant that he’s cooking and it’s a false alarm. That silences the buzzer, but not before the system responds with a message questioning his skills in the kitchen. It’s a simple quality of life improvement and it’s certainly not hard to imagine how the idea could be expanded upon to notify you of a possible situation even when you’re out of the home.

We’ve seen how a series of small problems can cascade into a life-threatening situation. If you’re going to perform similar experiments, make sure you’ve got a “dumb” smoke alarm as a backup.

Continue reading “Building A Smarter Smoke Alarm With The ESP8266”