If you live somewhere cold, where the rain, snow and slush don’t abate for weeks at a time, you’ve probably dealt with wet boots. On top of the obvious discomfort, this can lead to problems with mold and cause blisters during extended wear. For this reason, boot dryers exist. [mark] had a MaxxDry model that had a timer, but it wasn’t quite working the way he desired. Naturally, it was begging to be hooked up to the Internet of Things.

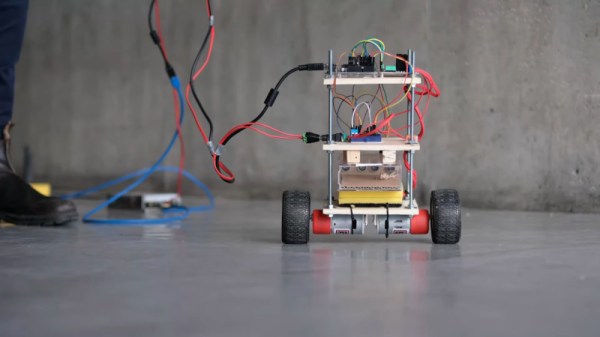

The brains of the dryer is an ESP32, a solid choice for such a project. With WiFi on board, connecting the device to the internet is a snap. Relays are used to control the fan and heater inside the boot dryer, while MQTT helps make the device controllable remotely. It can be manually switched on and off, or controlled to always switch on at a certain time of the day.

It’s a simple project that shows how easily a device can be Internet controlled with modern hardware. For the price of a cheap devboard and a couple of relays, [mark] now has a more functional dryer, and toasty feet to boot.

We don’t see a lot of boot hacks here, but this magnet-equipped footwear is quite impressive.