What is this world coming to when you can’t even enjoy sitting in your living room without some jamoke flying a drone in through the window? Is nothing sacred? Won’t someone think of the children?

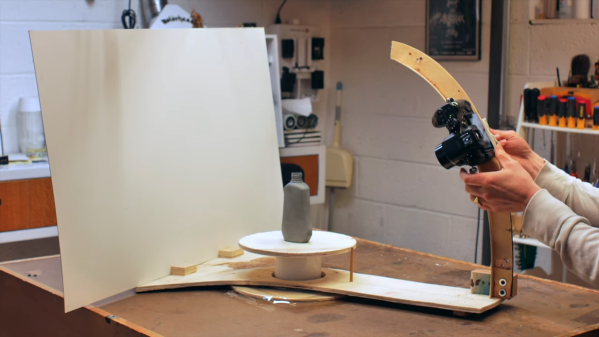

Apparently [Drew Pilcher] did, and the result is this anti-drone sentry gun. It’s a sturdily built machine – one might even say it’s overbuilt. The gimbal is made from machined steel pieces, and the swivels are a pair of Sherline stepper-controlled rotary tables with 1/40 of a degree accuracy selling for $400 each. Riding atop that is a Nerf rifle, which is cocked by a stepper-actuated linear slide, as well as a Kinect for object tracking. The tracking app is a little rough – just OpenCV hacked onto the Kinect SDK – but good enough for testing. The gun tracks as smoothly as one would expect given the expensive hardware, and the auto-cocking feature works well if a bit slowly. Based as it is on Nerf technology, this sentry is only indicated for the control of the micro-drones seen in the snuff video below, but really, anyone afflicted by indoor infestations of Phantoms or Mavics has bigger problems to worry about.

Over-engineered? Perhaps, but it’s better than letting the menace of indoor drones go unanswered. And it’s far from the first sentry gun we’ve seen, targeting everything from cats to squirrels using lasers, paintballs, and even plain water.

Continue reading “Well-Built Sentry Gun Addresses The Menace Of Indoor Micro-UAVs”