Everyone’s favorite viscoelastic non-Newtonian fluid has a new use, besides bouncing, stretching, and getting caught in your kid’s hair. Yes, it’s Silly Putty, and when mixed with graphene it turns out to make a dandy force sensor.

To be clear, [Jonathan Coleman] and his colleagues at Trinity College in Dublin aren’t buying the familiar plastic eggs from the local toy store for their experiments. They’re making they’re own silicone polymers, but their methods (listed in this paywalled article from the journal Science) are actually easy to replicate. They just mix silicone oil, or polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), with boric acid, and apply a little heat. The boron compound cross-links the PDMS and makes a substance very similar to the bouncy putty. The lab also synthesizes its own graphene by sonicating graphite in a solvent and isolating the graphene with centrifugation and filtration; that might be a little hard for the home gamer to accomplish, but we’ve covered a DIY synthesis before, so it should be possible.

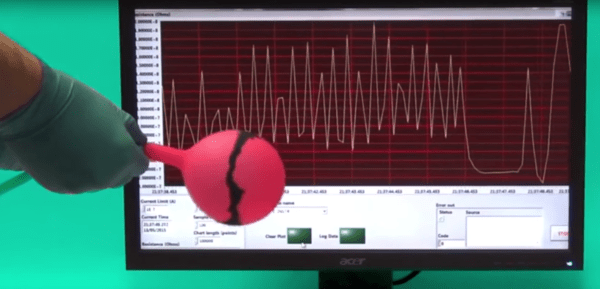

With the raw materials in hand, it’s a simple matter of mixing and kneading, and you’ve got a flexible, stretchable sensor. [Coleman] et al report using sensors fashioned from the mixture to detect the pulse in the carotid artery and even watch the footsteps of a spider. It looks like fun stuff to play with, and we can see tons of applications for flexible, inert strain sensors like these.

Continue reading “Flexible, Sensitive Sensors From Silly Putty And Graphene”