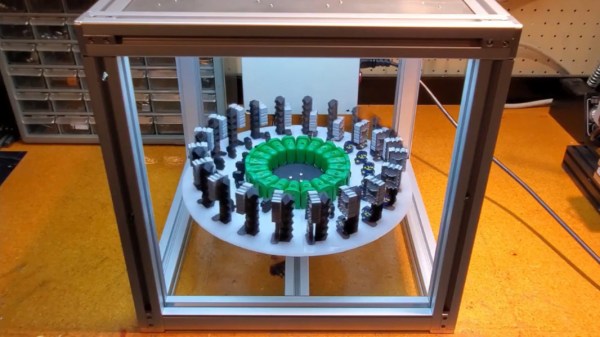

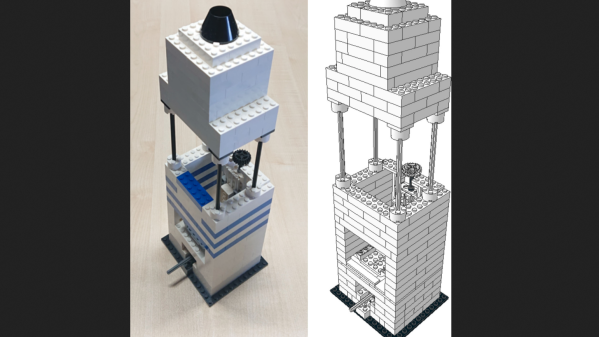

3D printing is all well and good if you want one of something, but if you want lots of plastic parts that are all largely identical, you should consider injection molding. You can pay someone to do this for you, or, in true hacker fashion, you can build an entire injection molding setup in your own garage, as [Action BOX] did.

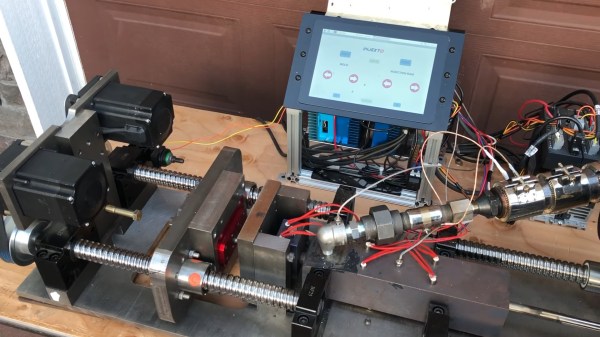

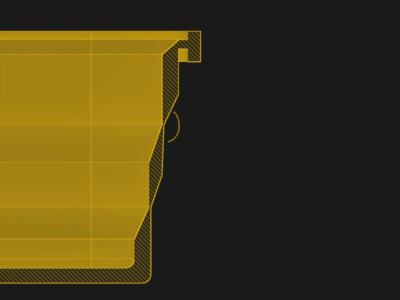

The build relies on a pair of beefy 3hp motors to drive the screw-based injection system. These are responsible for feeding plastic pellets from a hopper and then melting them and filling the injection reservoir, before then forcing the hot plastic into the mold. Further stepper motors handle clamping the mold and then releasing it and ejecting the finished part. A Raspberry Pi handles the operation of the machine, and is configured with a custom Python program that is capable of proper cycle operation. At its peak, the machine can produce up to 4 parts per minute.

It’s an impressive piece of industrial-type hardware. If you want to produce a lot of plastic things in your own facility, a machine like this is very much the way to go. It’s not the first machine of its type we’ve seen, either! Video after the break. Continue reading “A Plastic Injection Machine You Can Use At Home”