If you are an American Electronics Enthusiast of a Certain Age, you will have misty-eyed reminiscences of the days when every shopping mall had a Radio Shack store. If you are a Brit, the name that will bring similar reminiscences to those Radio Shack ones from your American friends is Maplin. They may be less important to our community than they once would have been so this is a story from the financial pages; it has been announced that the Maplin chain is for sale.

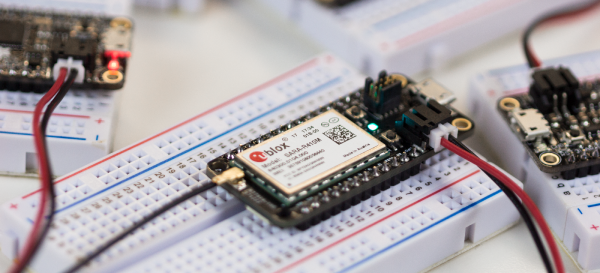

Maplin started life as a small mail-order company supplying electronic parts, grew to become a large mail order company selling electronic parts, and them proceeded to a nationwide chain of stores occupying a similar niche to the one Radio Shack fitted into prior to their demise. They still sell electronic components, multimeters, and tools, but the bulk of their floor space is devoted to the more techy and hobbyist end of mass-market consumer electronics. As the competition from online retailers has intensified it is reported that the sale may be an attempt to avoid the company going into administration.

It’s fair to say that in our community they have something of a reputation of late for being not the cheapest source of parts, somewhere you go because you need something in a hurry rather than for a bargain. A friend of Hackaday remarked flippantly that the asking price for the company would be eleventy zillion pounds, which may provide some clues as to why custom hasn’t been so brisk. But for a period in the late 1970s through to the 1980s they were the only place for many of us to find parts, and their iconic catalogues with spaceships on their covers could be bought from the nationwide WH Smith newsagent chain alongside home computers such as the ZX Spectrum. It’s sad to say this, but if they did find themselves on the rocks we’d be sorry to see the name disappear, but we probably wouldn’t miss them in 2018.

One of the things Maplin were known for back in the day were their range of kits. We’ve shown you at least one in the past, this I/O port for a Sinclair ZX81.

Footnote: Does anyone still have any of the early Maplin catalogues with the spaceships on the cover? Ours perished decades ago, but we’d love to borrow one for a Retrotechtacular piece.

Maplin store images: Betty Longbottom [CC BY-SA 2.0], and Futurilla [CC BY-SA 2.0].