In the first part of this series, we took a look at a “toy” negative-differential-resistance circuit made from two ordinary transistors. Although this circuit allows experimentation with negative-resistance devices without the need to source rare parts, its performance is severely limited. This is not the case for actual tunnel diodes, which exploit quantum tunneling effects to create a negative differential resistance characteristic. While these two-terminal devices once ruled the fastest electronic designs, their use has fallen off dramatically with the rise of other technologies. As a result, the average electronics hacker probably has never encountered one. That ends today.

Due to the efficiencies of the modern on-line marketplace, these rare beasts of the diode world are not completely unobtainable. Although new-production diodes are difficult for individuals to get their hands on, a wide range of surplus tunnel diodes can still be found on eBay for as little as $1 each in lots of ten. While you’d be better off with any number of modern technologies for new designs, exploring the properties of these odd devices can be an interesting learning experience.

Due to the efficiencies of the modern on-line marketplace, these rare beasts of the diode world are not completely unobtainable. Although new-production diodes are difficult for individuals to get their hands on, a wide range of surplus tunnel diodes can still be found on eBay for as little as $1 each in lots of ten. While you’d be better off with any number of modern technologies for new designs, exploring the properties of these odd devices can be an interesting learning experience.

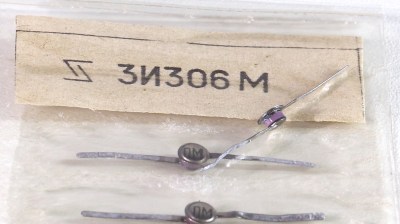

For this installment, I dug deep into my collection of semiconductor exotica for some Russian 3И306M gallium arsenide tunnel diodes that I purchased a few years ago. Let’s have a look at what you can do with just a diode — if it’s the right kind, that is.

[Note: the images are all small in the article; click them to get a full-sized version]

Continue reading “Fun With Negative Resistance II: Unobtanium Russian Tunnel Diodes”