Here at Hackaday we really like to feature projects that push the limits of what’s possible, or ones that feature some new and exciting technology that nobody has ever seen before. So what’s so exciting about this single-voltage linear power supply? Honestly, nothing — until you start looking at its thermally compensated current limiting circuit.

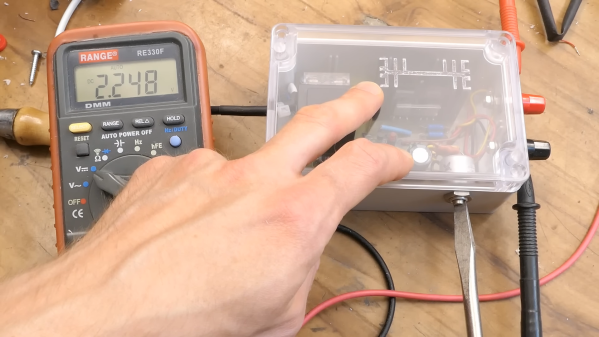

This one is by [DiodeGoneWild], who you’ve really got to hand it to in terms of both the empirical effort he went through to optimize the circuit, as well as the quality of his explanation. The basic circuit is dead simple: a transformer, a full-wave rectifier, an LD1085 adjustable regulator — a low-dropout version of the venerable LM317 — and associated filter caps and trimmer pot to adjust the output between 2.2 and 5.5 volts.

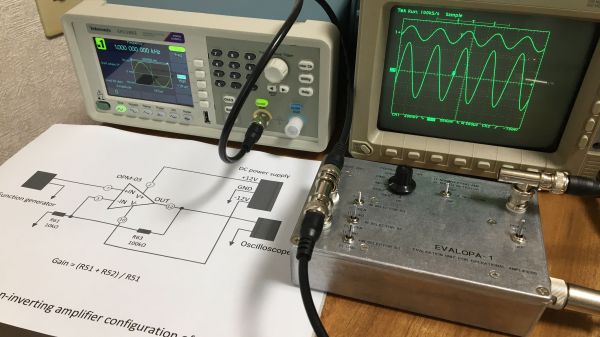

The current limiting circuit, though, is where things get interesting. Rather than use an op-amp, [DiodeGoneWild] chose a simple discrete transistor current-sense circuit. To make it less susceptible to thermal drift, he experimented with multiple configurations of resistors and Schottky diodes over a wide range of temperatures, from deep-freeze cold to hair-dryer-in-a-box hot. His data table and the resulting graph of current versus temperature are works of art, and they allowed him to make sensible component selections for a fixed 250-mA current limit with a reasonably flat thermal response.

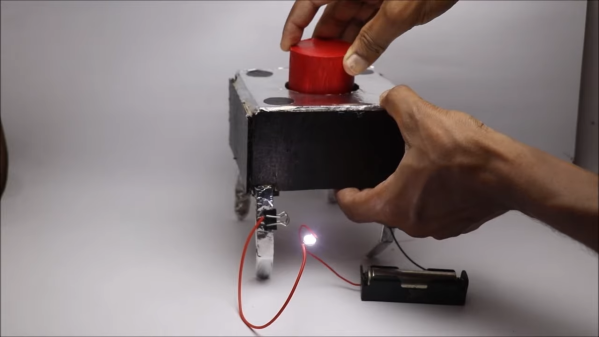

As for construction, it’s all classic [DiodeGoneWild], including a PCB with traces ground out with a Dremel and a recycled heat sink. He also dropped a couple of interesting build techniques, like adding leads to turn SMD tantalum caps into through-hole components. The video below shows all the build details along with the exhaustive breadboard testing.

From taking on a potentially risky magnetron teardown to harvesting lasers from headlights, there’s always something to learn from a [DiodeGoneWild] video.

Continue reading “Linear Power Supply’s Current Limiter Is A Lesson In Simplicity”