The promise of USB Power Delivery (USB-PD) is that we’ll eventually be able to power all our gadgets, at least the ones that draw less than 100 watts anyway, with just one adapter. Considering most of us are the proud owners of a box filled with assorted AC/DC adapters in all shapes and sizes, it’s certainly a very appealing prospect. But [Mansour Behabadi] hasn’t exactly been thrilled with the rate at which his sundry electronic devices have been jumping on the USB-PD bandwagon, so he decided to do something about it.

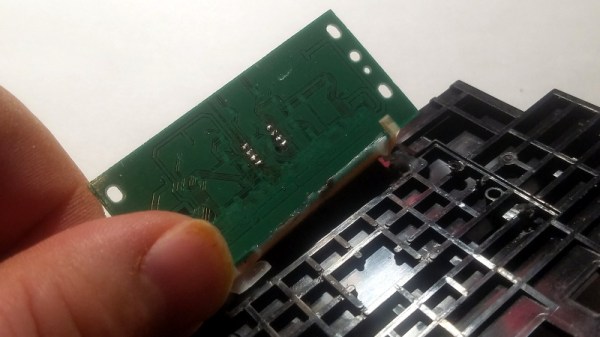

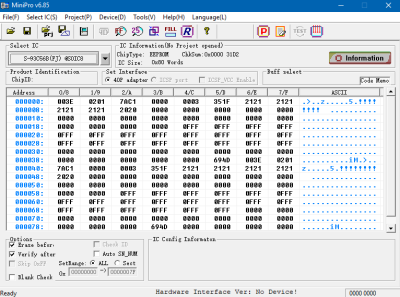

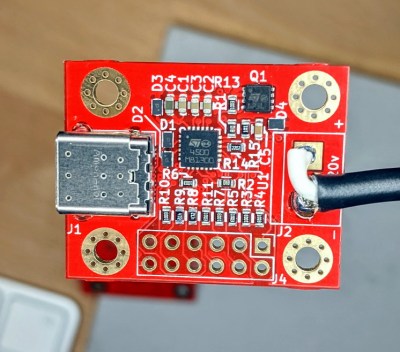

[Mansour] wanted a simple way to charge his laptop (and anything else he could think of) with USB-PD over USB-C, but none of the existing options on the market was quite what he wanted. He looked around and eventually discovered the STUSB4500, a a USB power delivery controller chip that can be configured over I2C.

[Mansour] wanted a simple way to charge his laptop (and anything else he could think of) with USB-PD over USB-C, but none of the existing options on the market was quite what he wanted. He looked around and eventually discovered the STUSB4500, a a USB power delivery controller chip that can be configured over I2C.

With a bit of nonvolatile memory onboard, it can retain its settings so he didn’t have to include a microcontroller in his design: just program it once and it can be used stand-alone to negotiate the appropriate voltage and current requirements when its plugged in.

The board that [Mansour] came up with is a handy way of powering your projects via USB-C without having to reinvent the wheel. Using the PC configuration tool and an Arduino to talk to the STUSB4500 over I2C, the board can be configured to deliver from 5 to 20 VDC to whatever device you connect to it. The chip is even capable of storing three seperate Power Delivery Output (PDO) configurations at once, so you can give it multiple voltage and current ranges to try and negotiate for.

In the past we’ve seen a somewhat similar project that used USB-PD to charge lithium polymer batteries. It certainly isn’t happening overnight, but it looks like we’re finally starting to see some real movement towards making USB-C the standard.