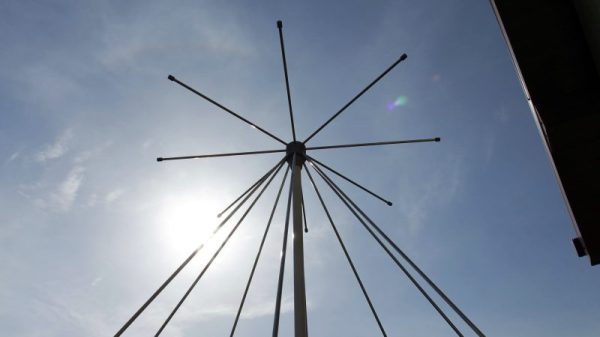

[Simon Aubury] owns a cat. Or perhaps it is the other way around, we can never really tell. One morning around 6AM, the cat — we don’t know its name — heard a low-flying aircraft and to signal its displeasure at the event, decided to jump onto [Simon’s] face as he slept. Thanks to the well-known mind control abilities of cats, [Simon] decided he had to know what plane was causing this scenario to recur. So he did what any of us what do. He used a Raspberry Pi and a software defined radio dongle to decode the ADS-B signals coming from nearby aircraft.

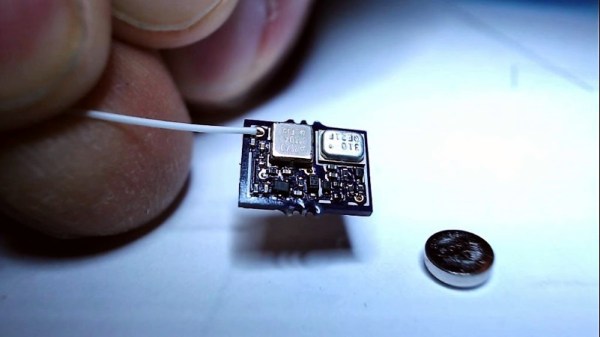

Picking up the signals and capturing them is easy thanks to the wide availability of USB radios and a program called Dump1090. However, the data is somewhat jumbled and not in a cat-friendly format. [Simon] turned to Apache Kafka — a tool for building real-time data pipelines — to process the data.