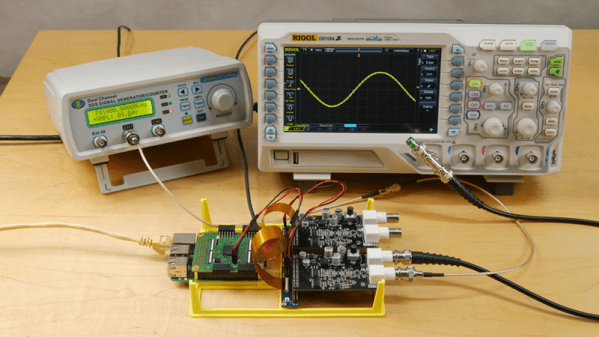

There are a multiplicity of transmission modes both new and old at the disposal of a radio amateur, but the leader of the pack is still single-sideband or SSB. An SSB transmitter emits the barest minimum of RF spectrum required to reconstitute an audio signal, only half of the mixer product between the audio and the RF carrier, and with the carrier removed. This makes SSB the most efficient of the analog voice modes, but at the expense of a complex piece of circuitry to generate it by analog means. Nevertheless, radio amateurs have produced some elegant designs for SSB transmitters, and this one for the 80m band from [VK3AJG] is a rather nice example even if it isn’t up-to-the-minute. What makes it rather special is that it relies on only one type of device, every one of its transistors is a BC547.

In design terms, it follows the lead set by other simple amateur transmitters, in that it has a 6 MHz crystal filter with a mixer at either end of it that switch roles on transmit or receive. It doesn’t use the bidirectional amplifiers popularised by VU2ESE’s Bitx design, instead, it selects transmit or receive using a set of diode switches. The power amplifier stretches the single-device ethos to the limit, by having multiple BC547s in parallel to deliver about half a watt.

While this transmitter specifies BC547s, it’s fair to say that many other devices could be substituted for this rather aged one. Radio amateurs have a tendency to stick with what they know and cling to obsolete devices, but within the appropriate specs a given bipolar transistor is very similar to any other bipolar transistor. Whatever device you use though, this design is simple enough that you don’t need to be a genius to build one.

Via [G4USP]. Thanks [2ftg] for the tip.