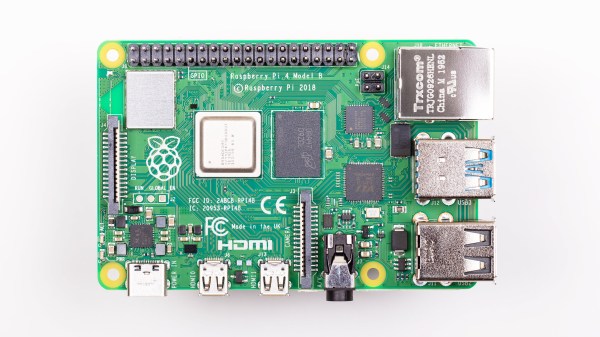

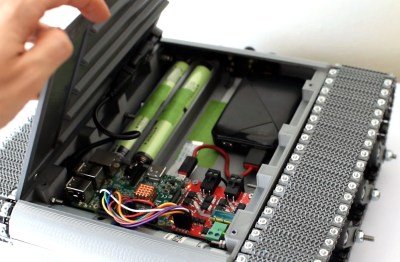

In the age of business Zoom rooms, having a crisp webcam is key for introducing fellow executives to your pet cat. Unfortunately, quality webcams are out of stock and building your own is out of the question. Or is it? [Dave Hunt] thought otherwise and cooked up the idea of using the Raspberry Pi’s USB on-the-go mode to stream video camera data over USB. [Huan Trong] then took it one step further, reimagining the project as a bootable system image. The result is showmewebcam, a Raspberry Pi image that transforms your Pi with an attached HQ camera module into a quality usb camera that boots in under 5 seconds.

Some of the project offerings on showmewebcam are truly stunning. Not only does the setup boot quickly, the current version requires a mere 64MB micro SD card for operations. What’s more, the project exposes camera settings like brightness, contrast, etc. via UVC, a standard USB protocol such that they can be controlled via typical software applications.

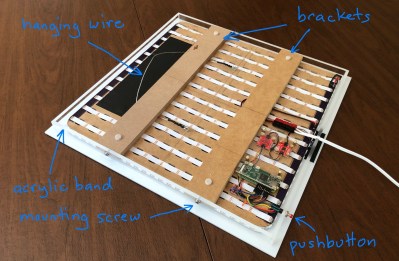

What’s truly exciting about this project is to see it take shape as different people tackle the same concept whilst referencing the prior milestone. [Dave Hunt] landed early to the scene with a blog post that established that the Pi could indeed be used as a USB webcam. [Huang Truong] built on that starting point, maturing it into an uploadable system image with notes to follow. Now, with showmewebcam on Github, it has seen contributions from over a dozen folks. Its performance specs are gradually improving. And it has a detailed wiki complete with suggested lenses and user-contributed cases to make your first webcam building experience a success.

And that’s not to say that others aren’t tackling this project from their own perspective either! For an alternate encapsulated solution, have a look at [Jeff Geerling’s] take on Pi-based USB webcams.

Continue reading “A Pi USB Webcam That Was Born To Boot Quick”